A CRITIC REMINISCES

Hope Silvestri was feisty. She would storm into my office (or cubicle or wherever I was calling home in the newspaper’s continuing obsession with reinventing its seating plan), fling herself into a chair, prop her elbow on the desk and say, “OK, young man … ”

Hope was passionate. In life, I mean. It was who she was. And she was especially passionate about theater. She regarded the newspaper as a means of getting the word out. She saw me as an obstacle that had to be either moved out of the way or lifted on board the bandwagon.

The paper never carried enough news about theater in her opinion. Opinion. Yeah, let’s talk about her opinion. She didn’t have just one, she had them by the cause-full. She shared them. She expected you to listen. And she was so devious. She listened to you.

Life was never dull with Hope.

And theater was never dull when Hope was on stage. As an actress, she was an elemental, a force of nature. She had an odd but appealing voice that she used to underline emotions, punch a comedy line and get the playwright’s message across in such a way that the patrons might not agree, but they could not ignore it.

By the time I was a regular in her audiences, Hope had gone through the ingenue and leading lady stages. Silver-haired, a bit stout, she played character parts. Didn’t bother her. In her opinion (yet another one), they were often the best roles. She certainly made them the best.

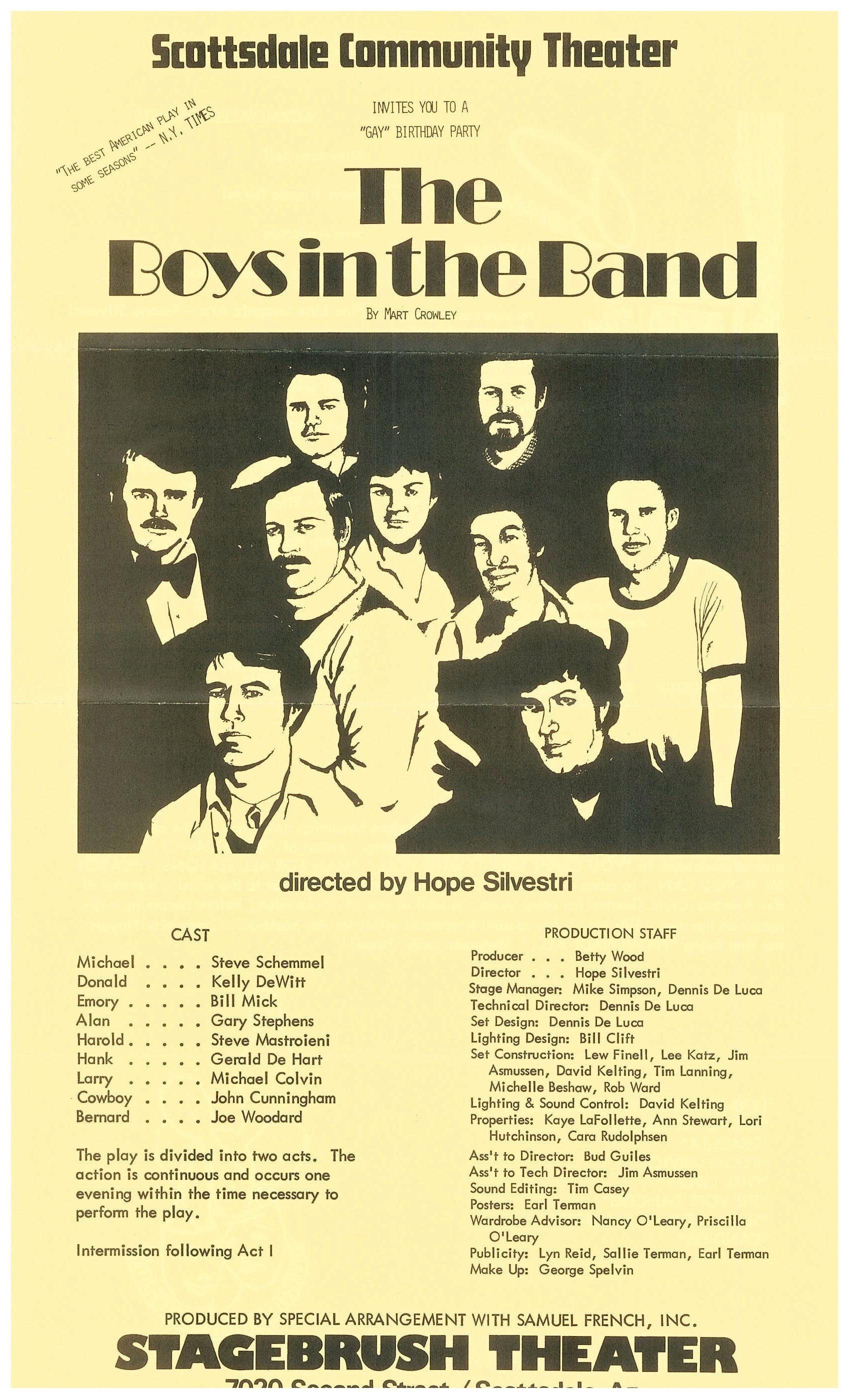

The first time I came under Hope’s microscope, I gained intimate knowledge of how an amoeba feels when it’s placed between the slides. She was wearing her director’s hat (as she sometimes did) and was determined to stage The Boys in the Band, the first overtly gay-themed play to gain wide acceptance. (Well, reasonably wide acceptance.)

She ran into one obstacle after another. I was the obstacle in the publicity department. Or the paper was. My bosses were concerned about how far we should go in publicizing the play. It was 1978. People didn’t expect to read about homosexuals with their coffee. She scrutinized every story, every lack of story. There were several meetings, often loud, one of them definitely confrontational. Hope made her points. She smiled. She cajoled. She scolded.

She got her way. The public was informed. The show went on. There were complaints, pickets, a million nuisances. They were trumped by praise and profit.

And Hope storming into the office. “OK, young man … ”

That, ladies and gentlemen, sums up Hope Silvestri as I remember her. Style and substance – and always another challenge.

*****

WE WERE NEVER THE SAME

Hope’s production of The Boys in the Band didn’t just change our thinking about gays as a subject for theater, it opened the door to plays about racism, sexual abuse, mental illness, abortion … so many things that were tearing our world apart. Seeing her success in getting the play produced, and witnessing the sold-out audiences and the money pouring in, encouraged a lot of on-the-fence producers to take a chance on controversial material. From that, alternative theater took root. All things are connected. Hope deserves her place in the pantheon of Valley theater icons.

*****

SOMETHING YOU MIGHT NOT KNOW ABOUT HOPE

Before moving to Scottsdale, Hope appeared in many plays in Tucson, including early works by the company that eventually became Arizona Theatre Company.

*****

THE PASSING

Hope Silvestri died in 1990. She was 65.

*****

PHOTOGRAPHS, REVIEWS & THE KITCHEN SINK

1981. “Whose Life Is It Anyway?” Phoenix Theatre.

Hope was a nurse looking after a paralyzed man who wanted to die in this gripping production. Despite its dark subject matter, the show was a hit.

*****

1978. “The Boys in the Band.” Scottsdale Community Theatre. Directed by Hope Silvestri.

An landmark production in the history of Valley theater this was the first overtly gay-themed play to be produced on a local stage.

1972. “Portrait of a Madonna.” Scottsdale Community Players. Directed by Ron Newcomer.

In this Tennessee Williams tale, Hope played a southern woman, jilted by her lover in her youth, who now lives in a nursing home and makes life miserable for everyone. Also in the cast were Steve Schemmel, Bob Klinkner, Jerry Gariff, Jane Graham and George Hetrick. Ron Newcomer handled the directing chores with Joan Allen as his producer. Sets were by Wally Kiel.

*****

1972. “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” CenterStage at the Jewish Community Center. Directed by Michael Lancy.

I don’t know much about CenterStage, a company whose name begins appearing in the archives in the late 1960s.

Many of the clippings involve the controversy that surrounded the 1972 production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

The show’s stars, Hope Silvestri and Steve Schemmel, were dropped from the cast two weeks before opening. Since both were popular performers, the papers jumped on the story.

The reason for the dismissals was never made clear. Hope told the Arizona Republic that she had asked director Michael Lancy to postpone the show for personal reasons and she thought he had agreed to the request.

Then she got her pink slip.

Steve told the Republic reporter that he had agreed to continue in the play without Hope. Then the director announced Steve had left the show to do another play.

Not true, Steve said.

“Lancy said that if he couldn’t do the show with the two of us, then he wouldn’t do it. We had no discussions of characterizations in our first rehearsals and his blocking made me a little bit nervous.”

Steve said that, despite what was announced, he did not leave to do a production of Child’s Play. “It’s a good show,” he said, “but it’s no Virginia Wolfe.”

There was some happy news regarding the production. A press release said the actors who replaced Hope and Steve – Angela Giron and Jimmie Wright – were to be married on stage after a performance. But even that turned out to be wrong. Angela, now living in Great Britain, says the ceremony didn’t happen.