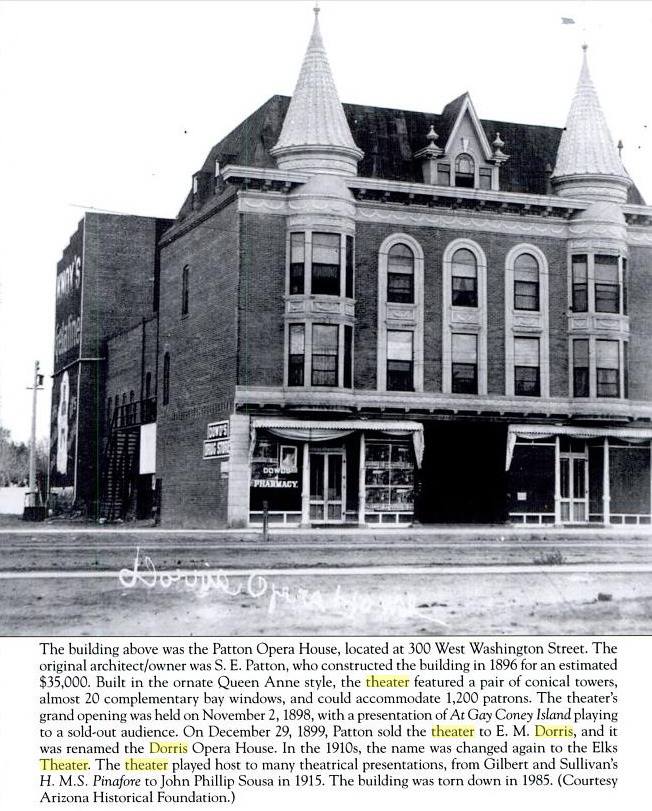

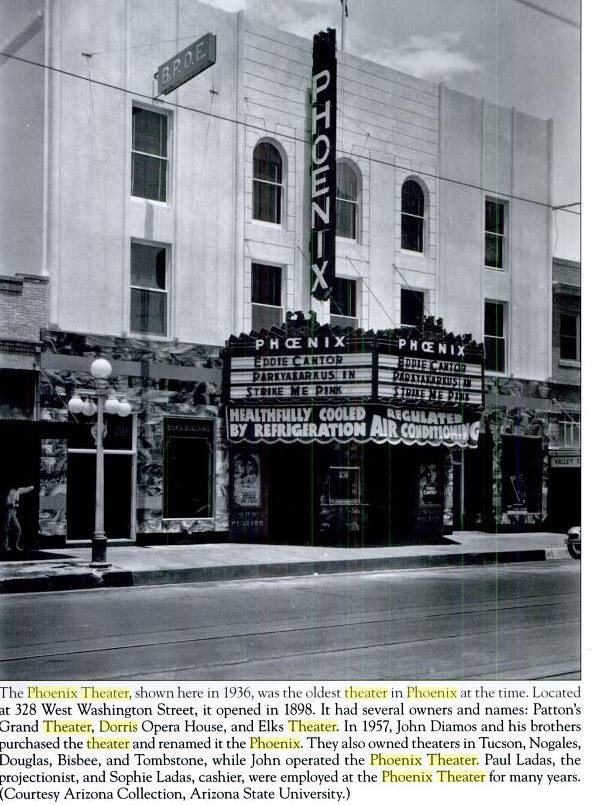

Located at 326 West Washington Street, in Phoenix, Arizona. The Dorris Opera House was built in 1898 and was the Herberger Theater Center of its day. Other names: Patton’s Grand Theater and, when it became a movie house, the Phoenix Theatre. It was heavily remodeled over the years and finally torn down.

For many years, the Elks Club was housed upstairs.

The building was three stories high with offices and two stores on each side at ground level. There was a simple marquee and vertical sign. After entering you had to walk down a long corridor to reach the theater in back.

There was a mural on the ceiling of three North American Indian maidens and Art Deco painted decoration.

For an interesting account of early Phoenix, including its theater operations, Philip VanderMeer’s “Desert Visions and the Making of Phoenix” is available as an E-Book. HERE

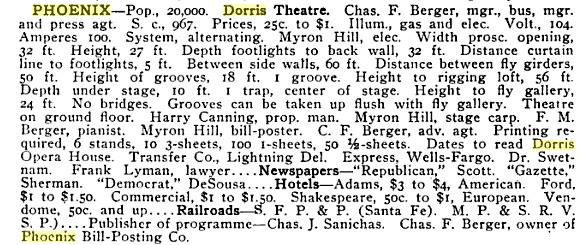

Here is the entry from the Julius Cahn-Gus Hill Theatrical Guide, unknown date.

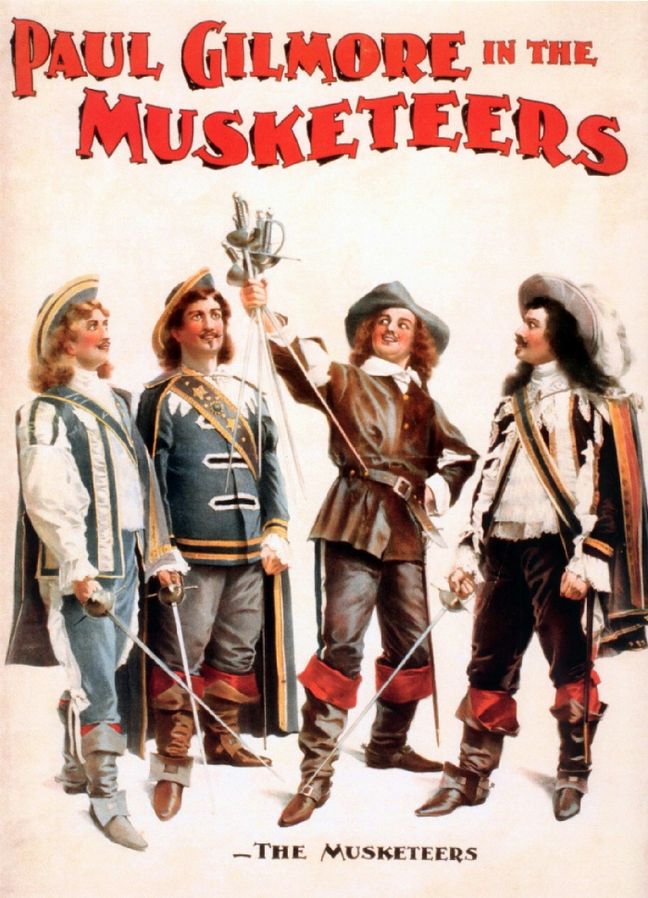

THE GREAT GILMORE MASSACRE

On Dec 16, 1899, the Dorris Theatre (or the Patton Grand, as it was known then) made national headlines when several members of the cast were severely injured during a battle scene in the touring production of Don Caesar. The chorus was armed with muskets with blank cartridges. Or so everyone thought. It turned out they weren’t blanks. Bang! Bang! And down the cast went, including Paul Gilmore, the star, who was shot in the knee.

The accident couldn’t have happened at a worse time for Gilmore, whose wife had died giving birth to twins just three months earlier. (The boy died in 1918, after jumping off a train on which he hitched a ride. The daughter later helped her dad manage New York’s famous Cherry Lane Theatre, where Robert Walker, Jennifer Jones, Carl Reiner and others got their start.)

Gilmore received six wounds, the most serious in his legs. He was at first not expected to live; when he did, doctors gave him little chance of being able to return to the stage. A bullet was removed from his knee in March 1900, after which he began to recover. By October of that year, he was again on the road, appearing in Under the Red Robe.

Unfortunately, actor Lewis Monroe died of lockjaw a month after the accident as the result of a bullet wound to the hand. For years afterward, the incident was referred to as the “great Gilmore massacre.”

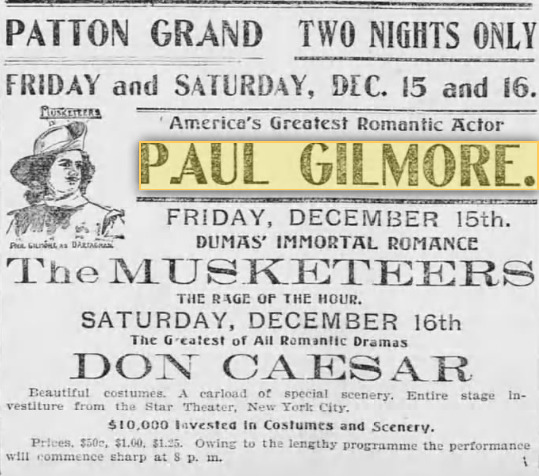

The first article announcing the company’s arrival, Dec. 15, 1899

The report of the shooting in the Dec. 17, 1899 edition of the Arizona Republican is odd. It clearly states the shooting occurred during a performance of Don Caesar, yet accounts in the New York Times and other papers and Gilmore’s biography state it was during a performance of The Three Musketeers. (On the other hand, the ads in the Republican indicate that it was Don Caesar that was scheduled to be performed that night). In any case, the paper failed to indicate the seriousness of the injuries. Gilmore very nearly died, and, later, another actor did. This could have been the case of an efficient publicity person toning down the incident so that future audiences wouldn’t have second thoughts about attending. Gilmore was the biggest draw for the tour, after all. If there were doubts he would continue, ticket sales would suffer. The article states that he would be back in on stage in Prescott. He was, on crutches, but after one performance, he was in such agony that he handed the part to his understudy.

IN DEFENSE OF THE REPUBLICAN, WE PRESENT …

The company’s newspaper ads clearly indicate that Don Caesar was on the bill that night, regardless of what the NYT and the biography say.

A FOLLOW-UP REPORT, Dec. 18, 1899 Arizona Republican

It wasn’t a good month for actors at the Patton Grand …

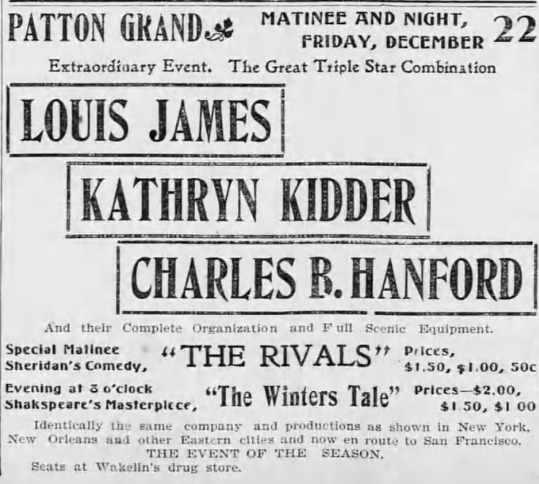

Kathrine Kidder scares the audience (and the management) when she pitches forward in a dead faint and whacks her head on the floor so hard it could be heard in the back row. This was just a few days after the shootout during another of the company’s productions, leading every one to think (and maybe rightfully so) that Paul Gilmore’s traveling troupe was jinxed.

Below is a clipping from the Dec. 8, 1902 Arizona Republican discussing Gilmore’s return to the Valley and offering a glimpse of the earlier chaos. Notice that this account states the shooting occurred during a performance of The Three Musketeers. Note also that Gilmore has undergone an upgrade in leading ladies. This time it’s the niece of a vice president of the United States.

LET US MAKE THAT PERFECTLY CLEAR …

Sometimes, digging in the archives of the Arizona Republican can leave you feeling as if you’ve just emptied the vodka bottle. In the early days, it would often print items from other papers and forget to credit them. This one, for example, looks like one of its own reviews, but it’s not until you read it that you realize it’s really a critique of a performance in Dubuque, Iowa! (And it ends in mid-sentence, too) Well, the show was coming to Phoenix and the piece gives you an idea of why people were so shocked when Paul Gilmore was shot two days later on the Dorris Opera House stage in what remains the most horrific theater accident in Phoenix history. That doesn’t happen to handsome young leading men. Usually.

PS: So where did the stars stay when they were in Phoenix? According to the Republican, Gilmore hied himself to the Adams Hotel. Lesser members of the company generally found lodgings at boarding houses. Black members of casts (and there were more of those than you would suspect) were usually put up at Miss Ellen’s Rooms to Let on Fourth Avenue. (Blacks were not allowed in the Adams, even as guests of guests.)

MAYBE WE’RE A JINX ….

Although Paul Gilmore returned to the Valley several times – his company always did land-office business – his connection to Phoenix was not a happy one.

Not only did he almost lose his life in the accident at the Dorris, one of his friends did. Then, a year later, his father came to Phoenix in hopes the desert climate would improve his health but, instead he died – on Dec. 18, the date Paul was shot at the Dorris. In 1902, Paul returned to Phoenix with his company and his new bride (his first wife died in childbirth). He took her to dinner at the Adams Hotel. She got a chicken bone in her throat and nearly chocked to death. The date? Dec. 18. Scary.

PHOTOGRAPHS, REVIEWS & THE KITCHEN SINK

- DECEMBER 1899. What Happened to Jones.

Is there such a thing as a perfect performance? The Arizona Republican of Dec 10 certainly thought so. It waxed enthusiastic over the touring What Happened to Jones at the Patton Grand.

- DECEMBER 1899. The Rivals, The Winter’s Tale.

Louis James was an actor-manager who believed that if it wasn’t broken, don’t try to fix it. For years, he mounted annual tours of (generally) classic plays featuring three headliners (one of whom was himself). Audiences grew used to this and came for the actors, the plays being the icing on the cake (or not). In this case, the formula was showing sides of audience boredom. The Rivals did not play to the capacity houses James had come to expect in Phoenix. The Winter’s Tale did a little better, helped by the publicity incurred with its leading lady did a dead faint during a performance, whacking her head on the floor with such a thud that it scared the … well, frightened the audience.

- Dec. 31, 1899 Arizona Republican. New Year’s Eve.

According to the Arizona Republican of Dec. 31, 1899, the New Year’s Eve program at the Dorris Theatre was Spider and Fly.

SOMEWHERE IN HERE, THE MANAGEMENT CHANGED AND THE PATTON GRAND BECAME THE DORRIS OPERA HO– USE, OR DORRIS THEATER AS IT WAS SOMETIMES CALLED.

- OCTOBER 1920. Ten Nights in a Bar Room.

” … a sensation unparalleled in the history of the drama.”

Apparently this was a temperance track disguised as theater. It promised “sobs and tears of sympathy from audiences of all sexes and ages” and a thorough trouncing of that “brutal, disgusting and demoralizing vice of drunkenness.”

- Dec. 1, 1900. Arizona Republic. Multiple Plays.

I’d buy tickets for most of these plays on the titles alone. The Devil and Company. Moths. What fun! But given this is 1900, I suspect Sapho is not what you might expect in 2014.

- DECEMBER 1900. The Star Boarder.

The Arizona Republican reprints an item from another paper to announced a play’s opening at the Dorris. Well, it saves on reporters’ salaries …

- DECEMBER 1901. Dorris Theater Advertisement.

In a letter to the editor published in the Dec. 15 issue of the Arizona Republican, a disgruntled theatergoer complained that the Dorris’ manager Nick Wagner was more interested in looking after his own interests than those of his patrons. That might possibly have been true, considering this strange advertisement that appeared in the same issue. Nothing like keeping it simple.

- JANUARY 1903. The Man from Mexico.

The publicity for this one promised a leading lady “of the blonde type.” I wonder if she came with jokes attached.

- JANUARY 1904, The Guilty Wife.

The Dorris Opera House, considered the finest theater in Phoenix, presented a “realistic melodrama” called The Guilty Wife to kick of the 1904 season. The Clyde Fitch script was a touring production taken on the road by the Della Pringle Company. During the week they were in town, the actors also staged Thelma, The Mansion of Aching Hearts and The Sultan’s Daughter. The hunk pictured in the Arizona Republican article is not identified.

Della Pringle was an actress popular in the 1890s and early 1900s. She first came to the public’s attention as a comedienne in the Western states and then moved east to Boston and New York, where she starred in a number of plays. She became famous enough to operate her own company, which toured the smaller markets in the American West. It was a life of ups and downs and ended on a down. She died a charity case in Boise, Idaho, at the age of 82.

- JANUARY 1904. The Fatal Wedding.

Theodore Kremer’s melodrama played to standing-room-only crowds at the Dorris. The same was true for other stops on the tour. It made a bundle for its producers, Sullivan, Harris & Woods. Local audiences appreciated the fact that the costumes, sets and lighting effects were exactly the same as they were in New York. “The scenic and mechanical effects are as spectacular as we had heard,” said the Arizona Republican. Drawing the biggest applause was a scene where the villain and the hero fought it out while suspended over a ravine on a rope.

- 1904 The Millionaire Tramp.

Lawrence Russell’s play is subtitled “A Vaudeville Melodrama Play All In One.” That is, every thing including the kitchen sink. By and large critics were not impressed.

They thought the vaudeville numbers could have been left out and the meller-drama would have been better. Wrote another: “You pay your entrance fee and get song and dance, an insane soliloquy, a real train of cars, a prize fight, otherwise known as a boxing contest, and incidentally a pastoral drama. It Is almost as good as a Christmas grab bag.” Still, the Arizona Republican’s mini-review (below) thought it “afforded pleasurable entertainment.”

The story? Something about a rich guy going on the road and meeting up with a mad physician, a wise-cracking hotel porter (played in blackface), a couple of rural bumpkins and the requisite pretty girl. Your guess is as good as mine as how a prize fight fit into all that.

- DECEMBER 9, 1905 “A Deserted Bride, “A Wise Woman.“

You have to love a show that guarantees 180 laughs a minute. Apparently “A Wise Woman” delivered.

- DECEMBER 1905. The Marriage of Kitty.

The theater world is a bit like Kevin Bacon. Six degrees of separation and all that. Paul Gilmore, the handsome young New York actor, had built a fan base in the Valley thanks to several appearances here. He knew Alice Johnson, from their days in New York. They talked about Phoenix (he had a lot to say: see above) and she expressed a wish to see the desert. She got her chance when she was asked to play the lead in A Friend of the Family. It stopped at the Dorris Theatre (as did most of the big tours) in 1903.

A Friend of the Family was produced by Jules Murry. Alice introduced him to Paul and he became Paul’s producer. Meanwhile, Jules had a new comedy, The Marriage of Kitty, ready for touring. At lunch one day, he told Paul he was having trouble casting the lead. Paul suggested Alice. Jules fondly recalled the excellent returns on A Friend of the Family. Though it was lighter fare than she was used to, Alice was back in Phoenix in 1905.

Kitty had a madcap plot involving fortune hunters, susceptible young women, gilded mansions and a lounge lizard or two. It was frothy enough to amuse audiences; one delighted critic said “it has absolutely no room for serious thought … (or) the semblance of a moral problem.” Alice had fun with her part: marry for money, repent at the casino and “what a lovely diamond necklace, how sweet of you.” Not to worry, she gets the man she really loves by curtain’s fall. Long, long lines at the box office.

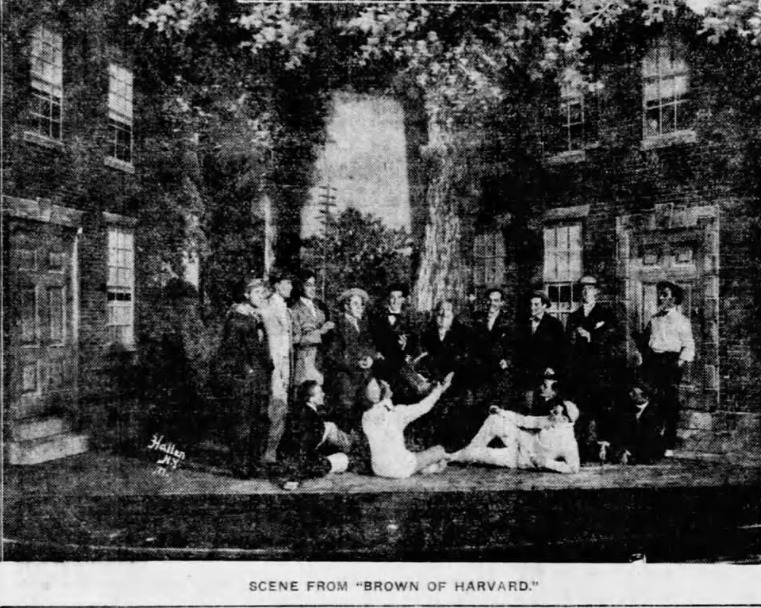

- DECEMBER 1907. Brown of Harvard.

Feminine hearts were aflutter when it was announced that the Dorris Opera House would host the touring company of Brown of Harvard, the college comedy that had taken New York by storm. The young actors playing the scholarly lads were reputed to be the most handsome men the producers could find. And there was a scene where they wore tennis shorts! Get the smelling salts, Ethel!

The manager of the Adams Hotel reported that the hotel had received “a great many inquiries” as to whether the actors would be staying there. Asked about the gender of those asking, he said “Young ladies. Entirely young ladies.” Young men apparently had other ways of gathering the information.

The comedy was written by Rida Johnson Young, forever to be known as the writer of the lyrics to “Mother Machree” and “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life.” She also wrote the lyrics for a couple of shows that would be forever identified with Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy, Maytime and Naughty Marietta.

Rida wrote the music for Brown of Harvard, too, but it really wasn’t a musical. It was the light-hearted tale of a cocky athlete who finds himself competing with a nerdy type for a professor’s daughter. Naturally, he gets his comeuppance, but his cheerful acceptance of being taught his manners endears him to his girl. All ends happily.

FYI: Three film versions were made. The first, a silent starring William Haines, marked the screen debut of John Wayne.