A CRITIC REMINISCES

Retirement is a time for many things. One of them is contemplation. I think a lot about the performers and productions I witnessed during my time as a theater critic in Phoenix. I am surprised (though I probably shouldn’t be) at how vividly some of those stand out in my memory.

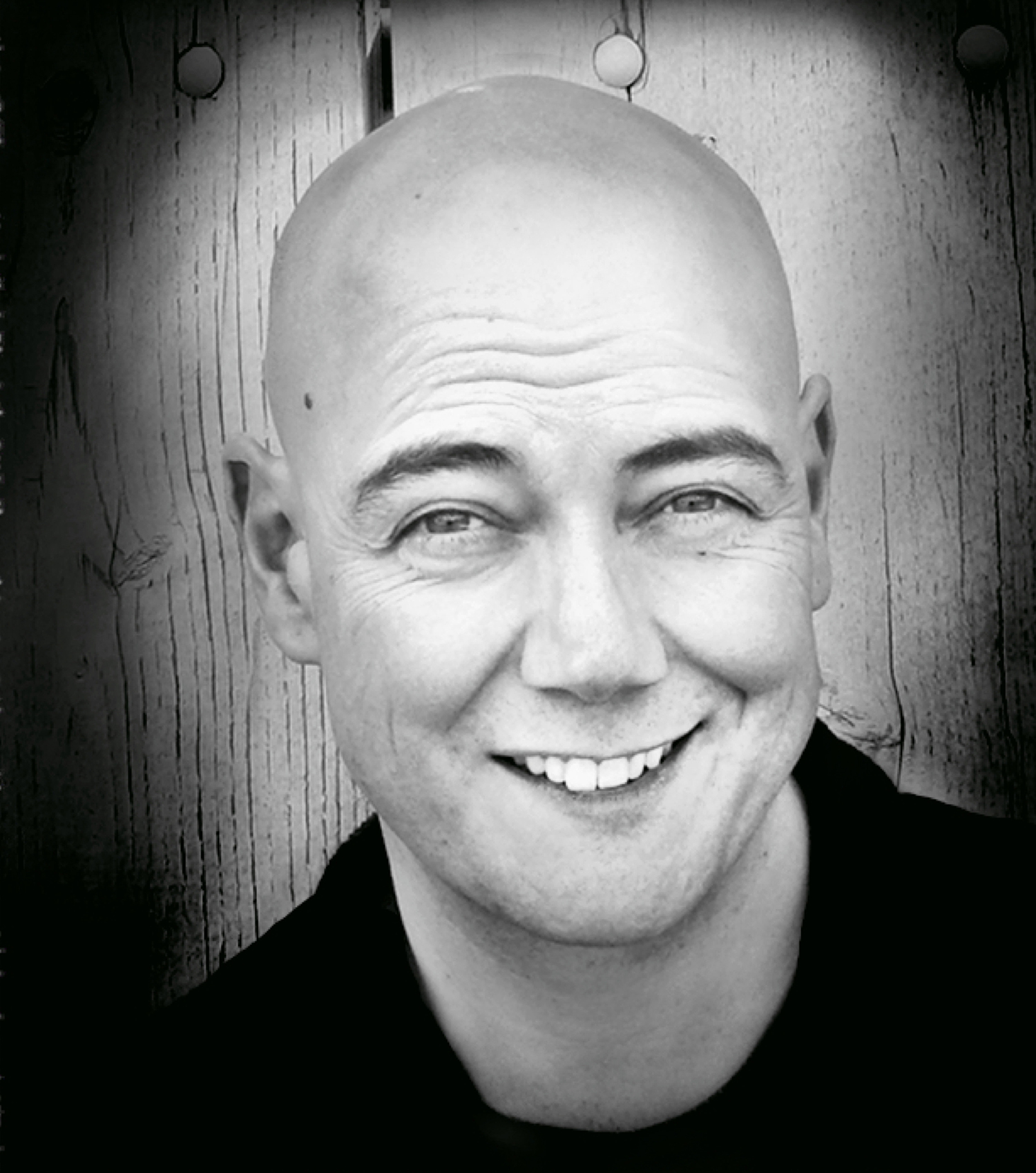

Andres Alcala is one of astonishing recollections, two of his performances in particular. In Guillermo Reyes’ Men on the Verge of a His-panic Breakdown,’ he actually played multiple roles. I don’t remember all of them, but some that stick in my mind were a jaded gigolo, a naive immigrant, an embittered teacher and a closeted middle-aged man.

It was like watching the proverbial hat trick performed by a maestro who had an unexpected surprise or two up his sleeve. I had to see the play twice, because the first time I was so dazzled by Andres that I couldn’t concentrate on Guillermo’s writing, which was by turns witty, poignant and subversive. I remember citing Andres as best actor that year. I don’t remember if I gave Guillermo anything but respect. Plenty of that, though.

The second performance was Andre’s Iago for Southwest Shakespeare in, I believe, though I am not sure, 1999. That Othello was a production of superlatives: Jared Sakren’s direction, Ken Love’s Othello, Maren Maclean’s Desdemona. But Andres’ Iago was the heart.

He was a frightening monster of a man, not because that is the character Shakespeare created, but because Andres gave him another of his twists. In his interpretation, Iago was a reasoned fellow who did what he did because he had no other choice. He explained this to the audience, and then, like Hitler after Mein Kampf, proceeded to do it, calmly, reasonably and horrifically. At one point, he actually caused a shiver to course down my spine.

It is for performances like that, and actors like Andre, that I revere theater.

BIOGRAPHY:

Andres has taught and performed with the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Oregon Children’s Theatre, Northwest Children’s theatre, ART’s actors to go, Miracle Theatre’s Pluma Nueva program and was an Associate Artist at Childsplay in Tempe, where he performed, directed and taught. He has received awards for acting and directing both in Arizona and in Oregon. Andrés toured as Ferdinand on the National Tour of Ferdinand the Bull with Childsplay 2010-11, which he also directed.

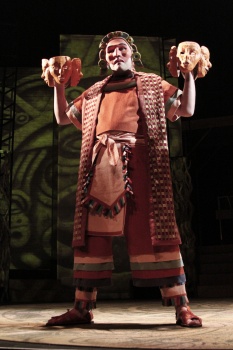

OCTOBER/NOVEMBER, 2011. THE SUN SERPENT.

Playwright: Jose Cruz Gonzalez. Director: Rachel Bowditch. Cast: Andres Alcala, others. Music, Sound: Daniel Valdez. Masks: Zarco Guerrero. Videography: Adam Larsen.

Note: “The Sun Serpent” was Childsplay’s contribution to the CALA Arts Festival, a two-month celebration of Latino culture in the Valley.

Article by Kerry Lengel, Arizona Republic

Most plays start their journey to the stage with a playwright at a keyboard. But “The Sun Serpent,” Childsplay’s multimedia epic about the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, began its life with six actors on yoga mats.

On Saturday, nearly two years later, it will debut as an intimate spectacle with shimmering video projections and a musical soundscape composed by Daniel Valdez of “Zoot Suit” fame. Dozens of characters will be portrayed by a trio of performers using masks created by Valley artist Zarco Guerrero.

“When I went to Veracruz and followed the path of Cortés’ army through the jungle to Mexico City, I felt like I was stepping into a whole different world,” says playwright José Cruz González. “I want the audience to experience the same thing I did. …

“This to me is like the ‘Iliad’ or the ‘Odyssey.’ It’s that huge in scale and scope, but we’re doing it with only three actors.”

González, who lives in California, has premiered half a dozen plays for young audiences at Tempe’s Childsplay, including “The Highest Heaven” and “Tomás and the Library Lady.” But though he is the writer of “The Sun Serpent,” he shares credit for its creation with many other artists. It is a “devised” work, an example of a growing trend in the theater.

The basic idea of devised theater is to break down the linear, hierarchical model of new-work creation, in which the playwright produces a draft, workshops and revises it, then hands it off to a director who guides the actors and designers. Instead, all of those creative voices come together at the beginning, improvising on themes and ideas to explore possibilities that a single artist could never imagine on his own.

While this is not exactly a new way to work, it is de rigueur. For example, devised work was the focus at the inaugural RADAR L.A. Festival, an international showcase of cutting-edge theater held in Los Angeles in June.

“The thing that distinguishes devising from the regular process is that the physicalization of the actors is just as important as the text,” says ” Serpent” director Rachel Bowditch. “Everyone has more of an equal voice. And that is becoming a trend because it allows people to create theater about things that haven’t been explored before.”

She adds, “Ninety-nine percent of devised theater is really, really bad. But the 1 percent that is good is the best theater that is out there.”

Bowditch, a professor in Arizona State University’s School of Theatre and Film, specializes in visual spectacle and movement-based performance — hence the yoga, among exercises she uses to get actors into a creative mode.

The first time Childsplay’s artists got together to work on “Sun Serpent,” they were prepared with a brief story proposal, about a young boy of the Totonac people who follows Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés to the Aztec capital, as well as plenty of research about pre-Columbian cultures and the history of the conquest. They selected props out of storage — toy swords, masks, a long sheet of China silk — and, essentially, played.

“It is very challenging,” says cast member Andrés Alcalá. “You’re given an idea, a seedling, and as actors we have to put all of our instincts, all of our training, all of our tools into effect and explore the possibilities.

“So we would come up with different ideas about what the cultural life would be like. We might tell a story with props and puppets in a smaller format, and then we would get it into a bigger scale and use fabric and masks to try to create that world.”

The silk turned out to be especially versatile. They used it to simulate ocean waves and an erupting volcano. At one point, Bowditch said, they considered building the entire show around that one piece of fabric.

After each devising session, González would spend hours writing. Together with the actors, he developed the plot into a conflict between two brothers, one who believes that Cortés is the god Quetzalcoatl, returned to free his people from the oppression of the Aztec emperor Moctezuma, and another who sees himself as part of a very different story.

The production design evolved similarly. The team settled on masks as the best way to create an array of characters with a cast of only three and brought in Chicano artist Zarco Guerrero, who is famed for his masks. He created nearly three dozen, each fitted to an individual actor’s face. There are Aztec faces and Spanish faces, a jaguar and a feathered serpent.

Video artist Adam Larsen, who has designed projections for theater and opera around the country, has created lush, painterly images to help move the story from seaside to jungle to the Aztec capital known as the City of Dreams. Composer Daniel Valdez, who wrote the music for “Zoot Suit,” used Spanish and native instruments to create the soundtrack.

All of these elements are integral to the storytelling.

“We’re actually able to show the codices, the pictorial symbols that tell the story of the conquest,” Alcalá says. “It also allows us to transform the stage into a jungle, to pretend like we’re underwater with moving video on these panels. It really allows the audience to take that leap of faith, that extra step into the magical world that we are creating onstage.”