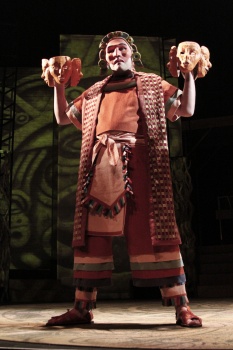

Playwright Jose Cruz Gonzalez, former playwright in residence at Childsplay. (Photo credit unknown).

Prominent Mexican-American playwright who was Playwright in Residence at Childsplay during the late 1990s and 2000s.

OCTOBER/NOVEMBER, 2011. CHILDSPLAY. THE SUN SERPENT.

Playwright: Jose Cruz Gonzalez. Director: Rachel Bowditch. Cast: Andres Alcala, others. Music, Sound: Daniel Valdez. Masks: Zarco Guerrero. Videography: Adam Larsen.

Note: “The Sun Serpent” was Childsplay’s contribution to the CALA Arts Festival, a two-month celebration of Latino culture in the Valley.

Article by Kerry Lengel, Arizona Republic

Most plays start their journey to the stage with a playwright at a keyboard. But “The Sun Serpent,” Childsplay’s multimedia epic about the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs, began its life with six actors on yoga mats.

On Saturday, nearly two years later, it will debut as an intimate spectacle with shimmering video projections and a musical soundscape composed by Daniel Valdez of “Zoot Suit” fame. Dozens of characters will be portrayed by a trio of performers using masks created by Valley artist Zarco Guerrero.

“When I went to Veracruz and followed the path of Cortés’ army through the jungle to Mexico City, I felt like I was stepping into a whole different world,” says playwright José Cruz González. “I want the audience to experience the same thing I did. …

“This to me is like the ‘Iliad’ or the ‘Odyssey.’ It’s that huge in scale and scope, but we’re doing it with only three actors.”

González, who lives in California, has premiered half a dozen plays for young audiences at Tempe’s Childsplay, including “The Highest Heaven” and “Tomás and the Library Lady.” But though he is the writer of “The Sun Serpent,” he shares credit for its creation with many other artists. It is a “devised” work, an example of a growing trend in the theater.

The basic idea of devised theater is to break down the linear, hierarchical model of new-work creation, in which the playwright produces a draft, workshops and revises it, then hands it off to a director who guides the actors and designers. Instead, all of those creative voices come together at the beginning, improvising on themes and ideas to explore possibilities that a single artist could never imagine on his own.

While this is not exactly a new way to work, it is de rigueur. For example, devised work was the focus at the inaugural RADAR L.A. Festival, an international showcase of cutting-edge theater held in Los Angeles in June.

“The thing that distinguishes devising from the regular process is that the physicalization of the actors is just as important as the text,” says ” Serpent” director Rachel Bowditch. “Everyone has more of an equal voice. And that is becoming a trend because it allows people to create theater about things that haven’t been explored before.”

She adds, “Ninety-nine percent of devised theater is really, really bad. But the 1 percent that is good is the best theater that is out there.”

Bowditch, a professor in Arizona State University’s School of Theatre and Film, specializes in visual spectacle and movement-based performance — hence the yoga, among exercises she uses to get actors into a creative mode.

The first time Childsplay’s artists got together to work on “Sun Serpent,” they were prepared with a brief story proposal, about a young boy of the Totonac people who follows Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés to the Aztec capital, as well as plenty of research about pre-Columbian cultures and the history of the conquest. They selected props out of storage — toy swords, masks, a long sheet of China silk — and, essentially, played.

“It is very challenging,” says cast member Andrés Alcalá. “You’re given an idea, a seedling, and as actors we have to put all of our instincts, all of our training, all of our tools into effect and explore the possibilities.

“So we would come up with different ideas about what the cultural life would be like. We might tell a story with props and puppets in a smaller format, and then we would get it into a bigger scale and use fabric and masks to try to create that world.”

The silk turned out to be especially versatile. They used it to simulate ocean waves and an erupting volcano. At one point, Bowditch said, they considered building the entire show around that one piece of fabric.

After each devising session, González would spend hours writing. Together with the actors, he developed the plot into a conflict between two brothers, one who believes that Cortés is the god Quetzalcoatl, returned to free his people from the oppression of the Aztec emperor Moctezuma, and another who sees himself as part of a very different story.

The production design evolved similarly. The team settled on masks as the best way to create an array of characters with a cast of only three and brought in Chicano artist Zarco Guerrero, who is famed for his masks. He created nearly three dozen, each fitted to an individual actor’s face. There are Aztec faces and Spanish faces, a jaguar and a feathered serpent.

Video artist Adam Larsen, who has designed projections for theater and opera around the country, has created lush, painterly images to help move the story from seaside to jungle to the Aztec capital known as the City of Dreams. Composer Daniel Valdez, who wrote the music for “Zoot Suit,” used Spanish and native instruments to create the soundtrack.

All of these elements are integral to the storytelling.

“We’re actually able to show the codices, the pictorial symbols that tell the story of the conquest,” Alcalá says. “It also allows us to transform the stage into a jungle, to pretend like we’re underwater with moving video on these panels. It really allows the audience to take that leap of faith, that extra step into the magical world that we are creating onstage.”

FEBRUARY, 1999. CHILDSPLAY. THE HIGHEST HEAVEN

Arizona Republic Review by Kyle Lawson

Too often, children’s theater is pablum: nutritious after a fashion but impossibly bland. Or worse, it’s junk food: the recycling of the same imagination-starved fairy tale.

Never at Childsplay. The company would rather stuff its young audiences with fare too sophisticated for its palate than blunt developing taste buds with cloying sweetness.

In The Highest Heaven, a world premiere at the Tempe Performing Arts Center, Jose Cruz Gonzalez, the troupe’s playwright in residence, has created a fable that is as appetizing for adults as it is for young people.

It is a cautionary tale of greed, passion and cruelty, and, at the same time, a magical enchantment that sends the senses soaring along with the monarch butterflies that are the focus of the story.

The settings are abstract, the plot revealed in shifting flashbacks. Director David Saar paces events quickly. The audience must pay attention to keep up, and to the credit of Gonzalez and the Childsplay artists, 2- and 3-year-olds were as raptly attentive at Saturday’s matinee as their older brothers and sisters.

Eavesdropping on the way to the parking lot, it was clear to this critic that everyone “got it.” Saar and his company risk going over the heads of their young audiences, but The Highest Heaven is proof that it is better to fail children at that level than to succeed by condescending to them.

Gonzalez’s play is the story of Huracan, a 12-year-old (Steven Pena) who is separated from his mother (Alejandra Garcia) in one of those forced deportations of aliens that blighted the government’s reaction to the Depression. He finds himself in a Mexican village, where he comes into conflict with the rapacious Dona Elena (Debra K. Stevens) and her toadying sons and nephews (all played by Jon Gentry).

Huracan finds shelter with El Negro (Ellen Benton), who, as it turns out, also has been evicted from America for reasons that the elderly Black hobo refuses to discuss. El Negro has become the protector of a forest reserve where monarch butterflies go every year to mate amid the lush vegetation – a verdant wonderland that Dona Elena wants to clear-cut to increase her already overflowing coffers.

Huracan is like one of the butterflies’ get, trapped in a chrysalis of naivete. With El Negro’s help, he breaks the bonds of childhood but discovers that freedom bears a draconian price tag. There are hard truths to be learned about ecology and economics, decency and friendship. The most painful lesson, and the most liberating, comes in realizing that life’s journey inevitably ends in death.

Gonzalez never belabors the moralizing or the butterfly metaphor, yet, when the monarchs spiral heavenward at the close (an exhilarating bit of stage magic), there are cheers from the audience and an understanding that Huracan has begun the perilous but life-affirming migration to adulthood.

Childsplay audiences have come to take excellent performances for granted, and the quintet of actors in The Highest Heaven does not disappoint. But Stevens’ versatility is exceptional even for this troupe. When last seen, she was the plucky young hero of The Velveteen Rabbit. Here she is a harpy from a child’s darkest nightmare, a chilling, malevolent presence that dominates the play even when off stage.

After more than a decade of dealing with Childsplay audiences, Stevens knows how far to take this. Just when Dona Elena is in danger of seriously frightening young playgoers, the actress does something so foolishly comic that they are startled into laughter. This is children’s theater, and she never forgets it – but at the same time, she never plays her audience for fools.

The same can be said of the company’s designers. The physical production represents state-of-the-art technology, but the effects are never used for cheap effect. Even at its most dazzling, the magic in The Highest Heaven has meaning. Sometimes, that meaning is subtle, but the assumption is: If the younger members of the audience don’t get it, the older ones will explain it.

It is a testimony to Childsplay’s skill at making theater that very little explanation is required.

INTERVIEW IN THE LOS ANGELES TIMES BY LYNNE HEFFLEY, FEB. 11, 2000

A frightened, lost boy’s odyssey of discovery and growth parallels the life of the migrating monarch butterfly in “The Highest Heaven,” a thought-provoking play now touring Southern California schools.

Playwright Jose Cruz Gonzalez said he was inspired by two somber realities: the racial tensions that he has observed between Latino and black youth in his work in schools, and the emotion-packed issue of immigration.

Gonzalez, associate professor of theater at Cal State L.A. and the former project director for the South Coast Repertory’s Hispanic Playwrights Initiative for 11 years, wove those themes into a spiritual and coming-of-age adventure undertaken by a 12-year-old boy during the Great Depression, when 400,000 people were involuntarily repatriated from the southwest United States to Mexico–“whether they were citizens or not,” Gonzalez said.

“My grandmother was a child on one of those trains,” he added.

The West Coast premiere of “The Highest Heaven” is being presented by the Mark Taper Forum’s theater company, P.L.A.Y. (Performing for Los Angeles Youth), after workshopping at the Kennedy Center in 1996 and then premiering at Childsplay in Arizona. The play is touring Southland elementary and secondary schools and will have several performances for the general public.

The play begins when 12-year-old Huracan is separated from his mother in the chaos of the forced repatriation. He ends up in a mountain village, hungry and alone, confronted by evil in the person of greedy landowner Dona Elena.

He finds both friend and father in a fellow sufferer, an isolated, elderly black man who has fled the States and a dark past and who now safeguards the monarch butterflies’ winter sanctuary.

“It brings these two people together,” Gonzalez said. “A boy who is searching for home, and an old man who is dealing with his ghosts. It’s not only about survival, but it’s about the spirit and soul. The old man, the awful thing he did on the other side, he has been trying to atone for; his question is, can I be forgiven? This little boy helps him in that.”

In return, the old man helps the boy find his inner strength and a new maturity.

“It doesn’t matter what color you are,” Gonzalez said. “It’s what’s inside of you. I think that was important to say to children. Here are two folks reaching out, searching, and they find each other and become parent and son to one another.”

Another message that Gonzalez hopes will come through the fantasy and the broad humor is “that no matter how dark it may be ahead, you will survive and you will get on in life. I think a lot of children are always struggling. It’s a message saying, ‘It [may] not be easy, but you’re going to be OK.’ ”

Director Diane Rodriguez, co-director of the Taper’s Latino Theatre Initiative, enhanced the play’s historic elements by having the actors initially portray traveling members of the Federal Theater Project of the 1930s, about to put on a show.

“We’ve really drawn from Depression-era music, too,” she said, “from black spirituals and Mexican corridos, all indigenous to that time period. And we have a lot ofa capella and song rounds.”

Rodriguez thinks audiences will enjoy the comedy–“the villainess [is] very frightful, but she’s very funny too”–but the friendship between the boy and the elderly man “is what’s going to hook the kids.”

The many images of the ethereal butterflies in the play are symbols of folklore and a metaphor for Huracan’s own blossoming from child to man. They also reflect themes of migration, fragility and strength.

“There are no borders for butterflies,” Gonzalez said. “It is a beautiful thing, a delicate thing, yet it survives this tremendous journey.” When the butterflies cluster in their sanctuary, “it’s like a sacred thing to see.

“I think that’s what children are.”