PHOTOGRAPHS, REVIEWS & THE KITCHEN SINK

*****

JULY 2000, “Quills,” In Mixed Company at the Herberger Theater Center.

INTERVIEW, Aug. 10, 2000. By Robrt Pela, Phoenix New Times.

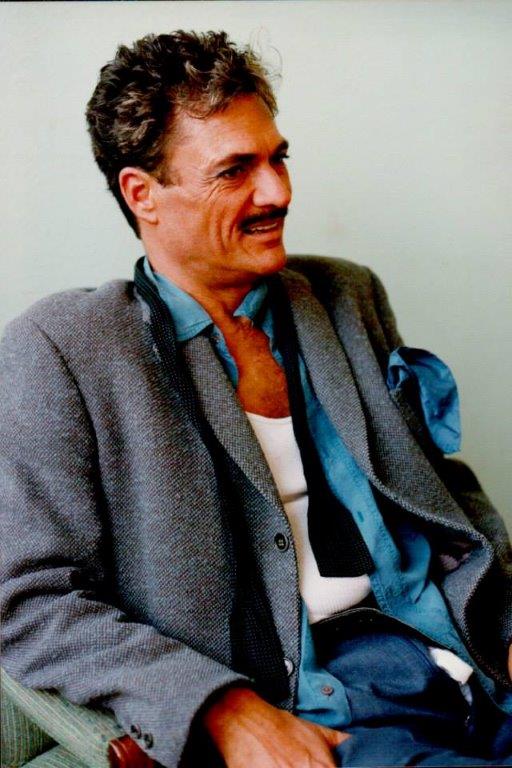

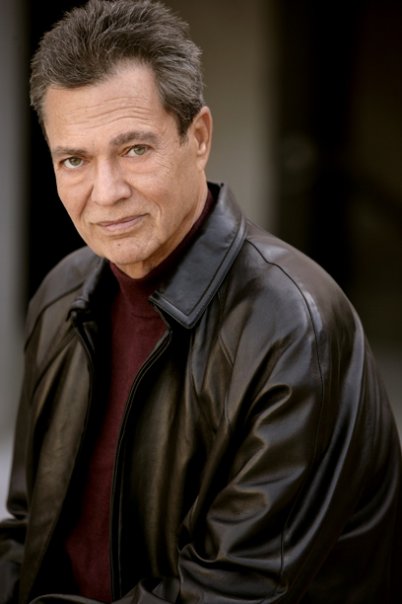

John Sankovich hasn’t once raised his voice, yet it booms above the clank and roar of the crowded restaurant where he’s dining. He’s discussing the 30-plus years he’s spent pacing local stages and — after a long hiatus — his return as the lead for In Mixed Company’s controversial Quills.

Above the din, his voice, like gravel frying in brown butter, is turning tiny stories into epics in which words like “no” contain five syllables. The role in Quills is Sankovich’s first in three years — a lifetime for an actor, and his longest absence since he began performing as a kid in 1962. He’s been preoccupied, reorganizing the family insurance business and recovering from his father’s death, which occurred during Sankovich’s last show, 1997’s Moon Over Buffalo.

Then again, the roles he’s been offered lately haven’t been particularly enticing. “Hey, I’m 50,” Sankovich says, making a sweeping gesture to indicate his still-slender frame and rugged good looks. “I’m making the transition from leading man to character actor, but I don’t exactly look like someone who can play Big Daddy in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.”

This demure appraisal is as close as Sankovich has come to conceit during the several hours we’ve spent recapping his career. Unlike most of the actors I’ve interviewed, Sankovich isn’t content to talk only about himself. He deflects compliments about his past work (“That was a fun show, but I could have been better in it.”) and interrupts questions about himself to recommend his colleagues (“They originally wanted David Vining to play the part I’m playing. He’s a really good actor!”).

If his humility is calculated, it’s also convincing. “The discovery that I didn’t have to act has been invaluable to my ego,” he says of his recent layoff. “Life used to be all about being seen in the next show. After being away, there’s a better balance.”

Which isn’t to say that Sankovich is considering retirement. He’s auditioning again, and, between performances of Quills, a moralist play about the Marquis de Sade, he’s scouting a producer for a one-man show about the Barrymores. The inspiration for that show, Sankovich says, came from yours truly: “Your last review of me claimed I was playing John, Lionel and Ethel all at once,” he says, arching an eyebrow. “So I figured maybe I should.”

It’s that Barrymoresque, bigger-than-life persona (imagine Robert Goulet crossed with Tallulah Bankhead) with which Sankovich has made a name for himself on local stages and in national touring companies. He’s logged three decades of consistently solid notices, in everything from Annie (he played Daddy Warbucks to Jo Anne Worley’s) to The Diary of Anne Frank. The Phoenix native is one among a handful of actors — Robyn Ferracane, Kathy Fitzgerald and Bob Sorenson are others — who ruled local stages for many years. If there’s such a thing as a Phoenix stage star (a term he wrinkles his nose at), John Sankovich is one of them.

“Whatever I am,” he booms, “it’s a far cry from the fat kid from West High who got beat up every day in the ’60s.” Back then, when Sankovich refused to defend himself against his attackers, his mother roped off the front yard and dragged the bullies into her makeshift bullpen. “She made me fight them,” he recalls, “but I didn’t know how to fight. So I sat on them.”

The 250-pound teen discovered that the stutter that plagued him vanished when he was onstage. “It’s such a clichéd story,” he says, “but it’s true. I started acting because it cured my speech problem. Not that I wasn’t a major hambone.”

The fat kid grew up, dumped a hundred pounds, and went on to work with everyone in the business. Pressed to drop names, he rattles off quick anecdotes with a bored shrug: “Streisand shows up prepared and gets a bad rap because she’s a perfectionist. Christopher Walken is shy; you barely know he’s in the room. Hans Conreid taught me to shop for cast recordings at the Salvation Army, and now I have every musical ever committed to vinyl.”

He prefers to tell stories — all of which seem to take place in Durant’s, where the big table in the corner is known as “The Sankovich Table” — about local actors who’ve moved on to higher climes. “Kathy Fitzgerald came in there for dinner last time she was in town, right after her baby was born,” he says. “She took out her tits and said, ‘John, look! One’s filled with chocolate, one’s filled with strawberry!’ She’s a nice married woman now, you know, playing Broadway. But she shows me her breasts in public. Another time Lisa Fineberg Malone got up on the bar and did an impersonation of Charo singing ‘Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.’ And no one was unhappy that she was dancing on their martinis.”

Most of his peers have defected: Fitzgerald to New York, Fineberg Malone to L.A. Sankovich misses the old days, but he’d rather talk about his new show than bemoan the past. “This is high melodrama,” Sankovich says of Quills. “It’s Dynasty on wheels!”

It’s also, he says, one of the hardest shows he’s ever done. “I have a master’s degree, and I had to have a fucking dictionary out while I was reading the script. I thought I knew what frottage was. And my speeches in French, well, don’t get me started.”

The play is a fictionalized tale of the notorious 19th-century writer whose name inspired the term “sadomasochism,” and whose indictments against his censors are the heart of this play. In Quills, de Sade has been incarcerated by Napoleon in an asylum, but refuses to stop writing sex stories. When he’s denied paper, he writes on his clothes; deprived of ink, he writes with his own blood.

Sankovich pulls out every stop as the Marquis, his performance an exhilarating mixture of acting genius and skillful camp. He reads de Sade’s pornographic parables with gleeful resonance, and chomps off quick hunks of dialogue (“We eat, we shit, we kill, and we die”) that describe the Marquis’ peculiar principles, all in that inimitable voice.

Sankovich is the only cast member who isn’t miked, and yet every nuance of his monologues — some of them 15 minutes long — is audible. His rolling timbre and feisty scenery-chewing is captivating. There are others in the cast, but — with the exception of Debra K. Stevens, who delivers a virtuoso turn as de Sade’s wife — none can keep up.

No matter. Sankovich’s performance is the centerpiece of the show, which — given its sexy subject and complicated language — he worries may be a tough sell.

“It’s not a short show,” he huffs. “It’s beautifully written, and really well staged, but intellectual. My opening speech is 15 minutes long! I wonder if people want to see smart shows anymore.”

The fact that Sankovich is naked throughout much of the program is another cause for concern, but one that provides him with a punch line. “That,” he sneers, “is reason enough for people to stay away!” Badump-bump.

After dinner, in the restaurant bar, Sankovich — cocktail in one hand, filter-tip in the other — has just finished an impersonation of Bebe Neuwirth doing “Mack the Knife.” Now he’s holding forth on “the great kids” he’s working with on Quills and why he’s been so lucky in his career. He’s been relentlessly upbeat all evening, and I’m trying to get him to talk about lousy actors he’s worked with. He isn’t biting.

“I don’t resent bad acting so much as bad manners,” he says. “You come to the stage unprepared, that’s unforgivable. You’re wasting other people’s time, and there are too many things in life you could be doing. Because, hey, take it from me. Acting isn’t everything. It’s great to be up on that stage, but it isn’t life.”

*****

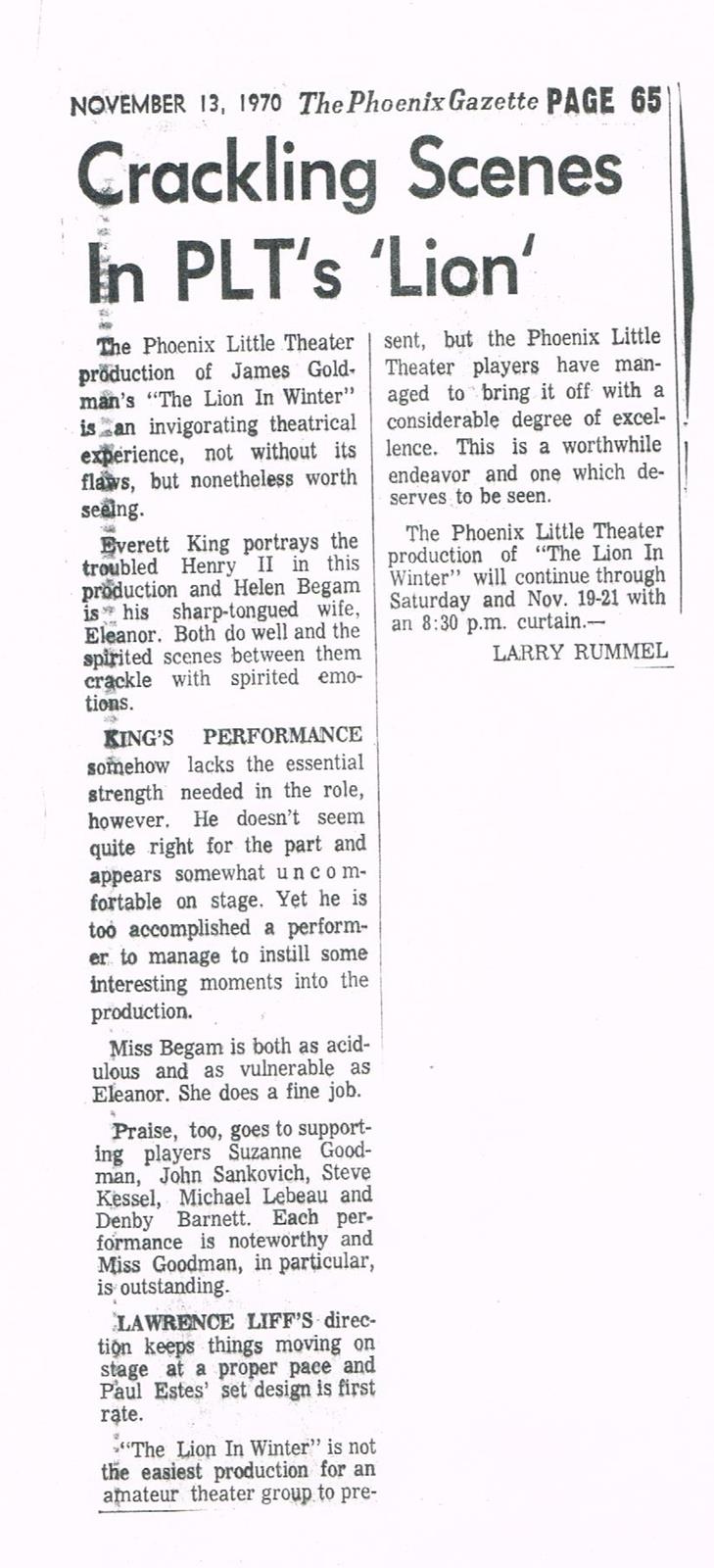

NOVEMBER 1970. “The Lion in Winter.” Phoenix Little Theatre. Director: Larry Liff. It’s funny how some productions have an apparently endless shelf life. I’m writing this in 2014, 43 years after Phoenix Little Theatre staged James Goldman’s comedy-drama, The Lion in Winter, and still people are talking about it. Although she was dismissed (albeit favorably) in three lines in Larry Rummel’s review, it is Helen Begam’s performance that seems to linger longest in the memory. Apparently she was magnificent. John Sankovich fans (they are legion, legion, I tell you) still recall his King Philip with a smile and, in any discussion of director Larry Liff, this play always seems to poke its nose into the conversation.

It’s funny how some productions have an apparently endless shelf life. I’m writing this in 2014, 43 years after Phoenix Little Theatre staged James Goldman’s comedy-drama, The Lion in Winter, and still people are talking about it. Although she was dismissed (albeit favorably) in three lines in Larry Rummel’s review, it is Helen Begam’s performance that seems to linger longest in the memory. Apparently she was magnificent. John Sankovich fans (they are legion, legion, I tell you) still recall his King Philip with a smile and, in any discussion of director Larry Liff, this play always seems to poke its nose into the conversation.

*****

******

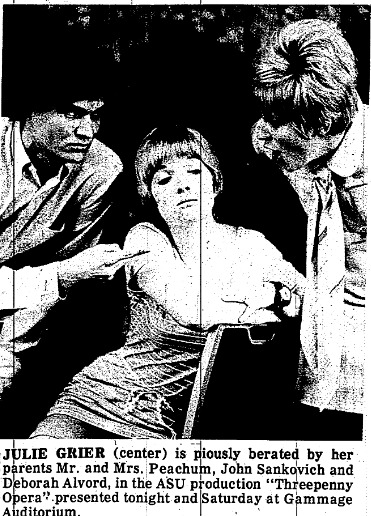

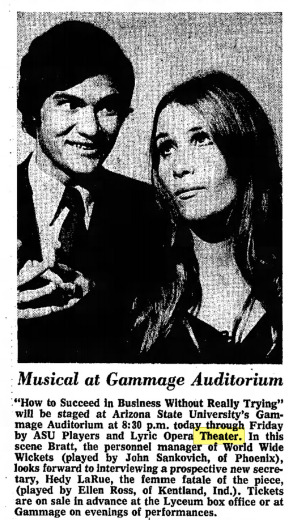

MAY 1970. “Threepenny Opera,” ASU Theater.

Photo from May 8, 1970 Scottsdale Daily Progress. Pictured are John Sankovich, Julie Grier and Deborah Alvord.

*****

John’s entry at the Internet Movie Base: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0762869/?ref_=fn_al_nm_1