ASU GAMMAGE TO HOST ‘BOOK OF MORMON’ TOUR

By Kerry Lengel, The Arizona Republic, April 28, 2014

Broadway buffs in metro Phoenix finally will get the chance to see “The Book of Mormon,” the critically acclaimed, cheerfully profane musical from the creators of “South Park” — but not for another year or so.

ASU Gammage, which hosts first-run Broadway tours, announced Monday, April 28, that the controversial hit will be part of its 2015-16 season. Dates and ticketing details are still to come.

“We’ve been fielding hundreds and hundreds of requests for the show, so we’re very fortunate that it will be here,” said Colleen Jennings-Roggensack, executive director of ASU Gammage, which is owned and operated by Arizona State University.

For many patrons who have been asking when “The Book of Mormon” will come here, the next question will be: Why did it take so long?

Gammage — a 3,000-seat auditorium designed by Frank Lloyd Wright that will mark its 50th anniversary this year — is one of the top Broadway touring houses in the country and often is one of the first venues to host the most popular shows. For example, when 2012’s Tony Award winner for best musical, “Kinky Boots,” comes to Tempe in September, it will be will be on its second stop after a tour launch in Las Vegas.

In contrast, 2011’s “The Book of Mormon” has been on the road for 18 months and played in scores of cities large and small, from Chicago and Atlanta on down to Schenectady, N.Y. The unexplained delay has fueled rampant rumors that Gammage avoided scheduling the show because of its controversial content — perhaps bowing to political pressure from influential members of the local Mormon community.

“At this stage of the game, we’re just so excited that the show is coming that I’m not going to comment on that,” Jennings-Roggensack said.

“When we have the show here, one of the things we’re going to talk about is it does contain explicit language, and we really want people to use their own judgment in making the decision to see the show. But we’ve always prided ourselves on having a diversity of patrons and a diversity of arts entertainment, so we’re just looking forward for people to familiarize themselves with all of our presentations, not just this one. We want them to make informed decisions.”

“The Book of Mormon,” created by “South Park’s” Trey Parker and Matt Stone along with “Avenue Q” and “Frozen” songwriter Robert Lopez, opened on Broadway in March 2011 to rave reviews and packed houses. That spring, it won nine Tony Awards, including best musical.

The plot involves two missionaries from Salt Lake City sent to preach in war-torn Uganda. Woefully unprepared to face the violence and poverty there, they suffer a crisis of conscious.

Satirical musical numbers include “You and Me (But Mostly Me),” a duet sung by chipper go-getter Elder Price and geeky companion Elder Cunningham, and “Spooky Mormon Hell Dream,” which features a giant dancing Starbucks cup (a reference to the Mormon prohibition on drinking coffee).

There’s also a spoof of “Hakuna Matata,” the don’t-worry-be-happy anthem from Disney’s “The Lion King,” that is, from nearly any religious perspective, wildly blasphemous.

Without question, much of the content is offensive to many members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Miles Abernethy of Gilbert, the owner of a graphic design firm and a former LDS bishop, is a fan of such Broadway shows as “Phantom” and “Cats” but said he would rather “The Book of Mormon” musical “not exist.”

“I love the Book of Mormon, and to me it’s the word of God, so to have a play out there that uses its name and profanes God to me is deeply concerning,” he said. “But people have their agency and people will do what people will do…. Hopefully, the honest in heart will want to have a broader picture of it all.”

Fans of the show, however, say that although it satirizes some aspects of Mormonism, it ultimately takes a positive view of the role faith plays in people’s lives.

Among those supporters is Chandler photographer Micah Nickolaisen, 30, who belongs to a Facebook group of “progressive and post-Mormons” with 400 members. In 2012, he says, about 30 or 40 of them met up for a road trip to see “The Book of Mormon” in Los Angeles.

“We all wore our white shirts and ties and our missionary tags to the show, and it was a blast,” he said.

“I think it’s important for all religious people to learn how to not take themselves so seriously, especially a more fundamentalist religion like Mormonism. It’s good to be able to laugh at ourselves.”

Nickolaisen says he will probably always identify as a Mormon but also relates to the musical’s message that “there’s value in religion above and beyond its literal truth.”

He likes the show so much, in fact, that he’s planning another group trip to see it in San Diego next month.

That’s the kind of passion that has “The Book of Mormon” selling out venues across the country, and not just in politically blue states.

Before it comes to Tempe, the show will have played in Des Moines — twice — and in Salt Lake City, international headquarters of the LDS Church.

High demand also means high prices. At Keller Auditorium in Portland, Ore., which will host the musical for a two-week run in July, tickets for the few remaining good seats are running as high as $750.

At Gammage, Jennings-Roggensack said, “Our ’14-15 Broadway subscribers are going to have priority on those tickets. So that’s going to be the best way to see the show.”

HISTORY

Gammage is located on the Tempe campus of Arizona State University. It is among the largest university-based presenters of performing arts in the world. ASU Gammage is the home theater of the Broadway Across America series and the Beyond series. ASU Gammage is an historic hall designed by internationally renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

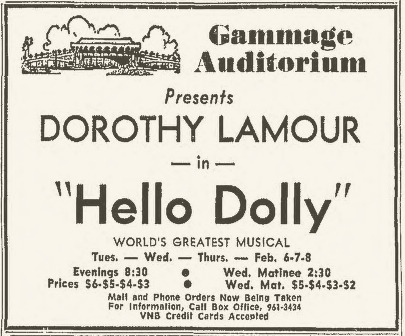

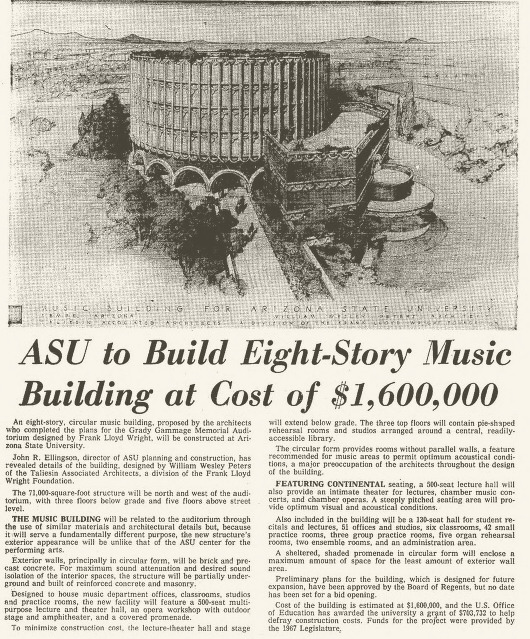

In 1957, ASU past President Grady Gammage had a vision to create a distinct university auditorium on the campus of Arizona State University (ASU). He called on close friend and famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright to assist with the project. As luck would have, Wright had a design prepared for an opera house in Baghdad, Iraq that did not come to fruition that he decided to use for this theater.

During a tour of the campus, Wright took a liking to an athletic field and said, “I believe this is the site. The structure should be circular in design and yes, with outstretched arms, saying ‘Welcome to ASU!'” Wright worked on the sketches for the building during the last two years of his life. His most trusted aide, William Welsey Peters, brought his plans to finished form.

Neither Wright nor Gammage lived to see the transformation of the blueprints, but their vision instantly became an iconic venue under the new direction of R.E. McKee Company from El Paso, N.M. to complete the construction. In 1962, Grady Gammage, Jr. turned the first shovel of dirt in the official groundbreaking.

Construction of the $2.46 million building took 25 months. ASU Gammage stands 80 feet high, eight stories by normal building standards, and measures 300 by 250 feet. Two pedestrian bridges add to the feeling of vastness, and extend 200 feet like welcoming arms. ASU Gammage was completed in September 1964. ASU Gammage is the only public building in Arizona designed by Wright.

The 3,000-seat performance hall offers three levels of seating, with the furthest seat only 115 feet from the stage. The acoustics are well balanced for unamplified performance, and the floating design of the grand tier assures an even flow of sound to every seat.

The stage can be adapted for grand opera, musical and dramatic productions or for symphony concerts, organ recitals, chamber music recitals, solo performances and lectures. The remarkable versatility of the stage is enhanced by a collapsible orchestra shell which, when fully extended, can accommodate a full orchestra, chorus and pipe organ. The shell is telescoped into a specially designed storage area when not in use.

ASU Gammage celebrated its grand opening with great fanfare on September 18, 1964. Under the baton of legendary conductor Eugene Ormandy, The Philadelphia Orchestra filled the hall with a history making first performance. The first Broadway production was in 1964 and was Camelot. For the next 30 years, ASU Gammage was host to many national and international dance companies including Alvin Alley Dance Company, Boston Ballet, Martha Graham Dance Company, Joffrey Ballet and Broadway productions as well as legendary musicians including B.B. King, Neil Diamond, Bruce Springsteen, Johnny Cash and Elton John.

Since it opened, ASU Gammage has had five executive directors, David Scoular 1964-74, Warren Sumners, 1974-79, Miriam Boegel 1979-84, Jim O’Connell 1984-91 and Colleen Jennings-Roggensack has served since 1991. Jennings-Roggensack has artistic, fiscal and administrative responsibility for ASU Gammage, ASU Kerr Cultural Center, with additional responsibility for non-athletic activities at Sun Devil Stadium and Wells Fargo Arena.

In 1991, Colleen Jennings-Roggensack took the helm as executive director and established the mission of Connecting CommunitiesTM. The organizational mission of Connecting CommunitiesTM allows Gammage to go beyond its doors to change lives for the better and make a difference in our community through the shared experience of the arts. Through this initiative, Gammage has discovered and created new avenues of communication through the arts to bridge cultural, economic and geographic divides. Along with its mission, Cultural Participation programs have been created that take artists’ work into classrooms and community organizations so that patrons of all ages and backgrounds can reap the benefits of arts involvement. For young people in particular, those benefits can be profound. Studies have shown that students who are involved in the arts perform better academically, are more involved in community affairs, have higher self-esteem and better attitudes toward school, and are less likely to drop out.

In Arizona, more than 134,000 students attend a school without any access to arts instruction and ASU Gammage provides numerous programs that give K-12 and university students opportunities to experience the arts through artist residencies, teacher development workshops and curriculum based programs that meet state arts education standards. Through a long-standing partnership with the Kennedy Center, ASU Gammage brings artist-mentors to Valley schools to work with teachers on integrating visual arts, dance, drama and music into mathematics, social studies, language arts and science lessons. By integrating the arts into other core subjects, teachers increase student engagement and make learning more relevant and meaningful.

Experiencing art communally with others also creates and strengthens social bonds, leading to an increased feeling of trust, mutual understanding and shared values that are vital for a healthy community. Exposure to the arts can even convey health benefits for people of all ages.

In the last 20 years, Jennings-Roggensack has commissioned 22 works to premiere at ASU Gammage which is more than any other presenter in the Southwest. Commissioned artists include Philip Glass, Trisha Brown, Bill T. Jones and the first North American commission of Pina Bausch.

Roggensack has also grown ASU Gammage into the largest university-based presenter of performing arts in the world. The Desert Schools Broadway Across America – Arizona series generates significant dollars, beyond the box office. The series is a leading economic engine for Tempe as well as the rest of the Valley. Even during difficult economic times, the series brought in nearly a billion dollars in economic impact to the Valley in the past 20 years. Since 1992, its estimated that ASU Gammage through its Broadway series brought in nearly $1 Billion of economic impact to Tempe as well as the rest of the Valley.

Since 1991, hundreds of well-known celebrities, musicians and performers have come through the theater as well including Mary J. Blige, Billy Crystal, Tony Bennett and Melissa Etheridge. Past artists include icons of dance, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolph Nureyev, Bill T. Jones and the Bolshoi Ballet and pillars of classical music, Vladimir Horowitz, Phillip Glass, Yo Yo Ma and Itzhak Perlman. Gammage also hosted the 2004 presidential debate, lectures, and symposiums featuring the world’s most prominent scientists, authors, dignitaries, politicians, and scholars, including Stephen Hawking, Elie Wiesel, Maya Angelou and Margaret Thatcher. ASU Gammage is also one of the major presenters of Touring Broadway and has presented significant productions including THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, WICKED, THE LION KING, MISS SAIGON, LES MISERABLES, ANGELS IN AMERICA, AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY, JERSEY BOYS and many more.

To ensure ASU Gammage remains a Valley icon for another 50 years, a 50th Anniversary Advisory Board has be established to work with the staff to help secure the future of ASU Gammage. Frank Lloyd Wright’s widow, Olgivanna, exclaimed that Gammage would be significant for centuries to come. “If this building is maintained, it will remain forever young,” she pronounced.

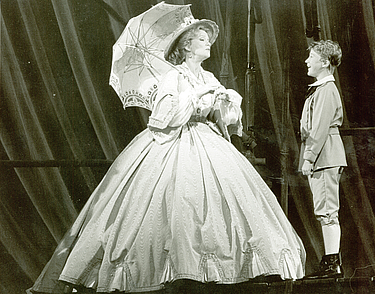

GAMMAGE AUDITORIUM. The King and I. Interview with star Hayley Mills. February 22, 1998|By Kyle Lawson ARIZONA REPUBLIC

Fans line up outside the stage door, but Hayley Mills can tell. They’re disappointed. Without her makeup from The King and I, she’s a woman. Pretty youthful for 50, maybe, but still grown up.

“You can’t stay 14 forever,” she says, but she doesn’t sound as if she expects anyone to believe it. Even her children went through a phase where they preferred the evidence of the videos. Cool, Mom, dig those great braids.

The actress knows that, daily, in some corner of the globe, her 14-year-old self tidies up everyone’s lives in Pollyanna and proves that two adults don’t stand a chance against twin teenagers in The Parent Trap. Her youth is preserved inside the planet’s VCRs like a prehistoric mosquito entombed in amber.

She is quick to say she doesn’t resent it, but in that world, she is forever on the verge of puberty, and that gets old even for a patient soul. When, as The King and I’s governess, she sings “Getting to Know You” to the children, she’s really offering the audience a chance to get to know her – not as she was, but as she is, a woman who managed to escape the deepest pitfalls of stardom but hit her fair share of potholes.

For some reason, those rough spots come as a surprise to fans. No one seeing her match wills with Vee Talmadge, her King and I co-star, will suspect she doubted she could do the role. Any more than audiences watching In Search of the Castaways or Summer Magic guessed that the actress was a mass of insecurities and victim of an eating disorder brought on by her conviction that she looked like a “piglet.”

If Mills has a mantra today, it is, “You can’t live your life safely.” Even so, the self-doubts haven’t been completely exorcised. It took the producers of the Australian tour of The King and I six months to persuade her to take the role.

“I’m glad that they did because the feedback from that tour led me to accept this American tour, and I’m having a wonderful time,” she says.

As for Mills’ early film career, repeated screenings of The Moonspinners, the 1964 thriller where she goes from child actor to romantic lead, offer the viewer no clues to the personal turmoil she was enduring. Away from the sound stages, however, she was so paranoid about her weight she was certain the crew wasn’t putting film in the camera for her close-ups.

“Next stop, lunatic asylum,” she said in a recent People interview. “What you want in front of the cameras is cheekbones and eyes that look like golf balls. It was a ridiculous thing. Constantly throwing up doesn’t do much for your self-esteem.”

Self-esteem would seem to have been the last thing lacking in the child who grew up on an English dairy farm. Unlike many show-business dynasties, the Mills clan is loving and close-knit. Her parents are Academy Award-winning actor Sir John Mills (Ryan’s Daughter) and novelist-playwright Mary Hayley Bell. Her older sister, Juliet, also is an actress and her younger brother, Jonathan, is a screenwriter and producer.

When she was 12, director J. Lee Thompson cast her as a girl who witnesses a murder in Tiger Bay. Lillian Disney saw the movie and nagged her husband, Walt, until he cast its youthful star in Pollyanna. The Disney movie put Mills in a class with Shirley Temple and Margaret O’Brien when it came to screen moppets.

Whatever problems she faced off-camera, Mills’ on-screen life remained charmed until 1966’s The Family Way, her first truly adult film, and one that featured a nude scene, a traumatic experience given her paranoia about her weight. The Family Way wasn’t popular, but the one good thing to come from the movie was her association with its director, Roy Boulting, 32 years her senior. They married in 1971 and are the parents of Crispian, 24, leader of the British band Kula Shaker.

In 1975, Mills met actor Leigh Lawson. Two years later, she ended her marriage to Boulting and moved in with Lawson, who’s the father of her son Jason, 20.

The relationship with Lawson ended in the early ’80s, sending her on a personal quest that seems to have borne fruit.

“I have learned that the important thing is to believe in God and to live your life according to spiritual truths,” she told People.

If Mills seems particularly footloose as she waltzes into “Shall We Dance?” it may be because she’s broken her most recent connection, a long association with rock musician Marcus Maclaine.

If there is anything Mills loathes talking about, it is her personal relationships, so she’s delighted, even if it is by this oblique method, to turn the conversation to The King and I.

“I love that scene,” she says. “There’s something indescribably romantic about wearing that dress and sweeping through the waltz in the arms of the king.”

The role has been “a big, big challenge, but I think I always would have been unhappy with myself if I had turned it down. I’ve done over 600 performances as Anna now and the play has become a bigger part of my life than the films, really.”

She studied with a vocal coach before taking on the part, which was originated on Broadway by Gertrude Lawrence opposite Yul Brynner in 1951 and re-created for the movies by Deborah Kerr, again opposite Brynner, in 1956.

Kerr, of course, didn’t sing in the film. Her voice was dubbed by Marni Nixon. Mills is aware that it is Nixon against whom she will be compared by audiences.

“I am not Marni and I am not Julie Andrews,” she says. “I do it the best way I can within my limitations.”

Mills says she realizes that people still connect her with her movies “and I’m grateful. I don’t wish those films had never happened, or that things would have been different. It’s true that I sometimes bemoan the fact that people still want me to be 14 and, yes, there were moments when everything wasn’t as perfect as it looked on screen, but it was a special time in my life, and I’m glad my work continues to give each succeeding generation pleasure.”

-30-

GAMMAGE AUDITORIUM. Miss Saigon. Jan. 10, 1999. Review By Kyle Lawson ARIZONA REPUBLIC

Maybe it was inevitable that our feelings toward Vietnam should come to this: a Gammage Auditorium audience standing and shouting its approval of a musical that knees America’s involvement in Southeast Asia in the groin.

The national cynicism toward the war is worn to the nub, the pain long ago turned to numbness. We are left with a sort of nostalgic curiosity about the past, and Miss Saigon gives us what we want.

It is madness restaged as a glitzy MGM musical, with a touch of Warner Bros. harshness and a generous heaping of Paramount romanticism. It can’t be a coincidence that one of the musical’s opening numbers is The Movie in My Mind.

We are movie-made America, after all, if not in our own sights, certainly in the world’s. Miss Saigon, we shouldn’t forget, was written by a pair of Frenchmen.

It may be one of the most successful musicals in history, but, as art, this extravaganza is wanting. Its characters have the depth of people in a Harlequin novel, the plotting is shamelessly manipulative, the music by Claude-Michel Schonberg isn’t a patch on his masterwork, Les Miserables. Alain Boublil’s lyrics come across as predictable and banal, though that may be the fault of Richard Maltby Jr., who translated them into English. Maltby’s lyrics for his own shows are proof all rhymers are not poets.

What Miss Saigon is, is a triumph of theatricality, and perhaps that is art of a kind. Producer Cameron Mackintosh and a team of inspired designers have cloaked the musical in scenes of such stunning imagery that its flaws almost disappear. The result is Brechtian in its epic sweep through the emotions.

The Gammage production is not the show it was in London, and it seems somewhat sparser than it did in New York, but scenic designer John Napier still serves up stage after stage of memorable set pieces. The helicopter lands on the roof of the Saigon embassy, Miss Liberty riding in a white Cadillac flies in from the skies, the towering statue of Ho Chi Minh rolls ponderously toward the front of the stage.

Lighting designer David Hersey bathes everything in a simmering stew of orange, scarlet and mustard, punctuated by cool blues and slashes of white.

Bob Avian’s dances are minispectacles in themselves, erotic and martial and thoroughly over the top.

It all is in service of what is, at heart, a schmaltzy operetta with a smutty mouth. Gammage audiences, usually conservative, seemed to take the gutter language and brothel antics of many scenes in stride. At least the men could appreciate the next-to-nothing costumes of the bar girls and the women the shirtless soldiers.

The spectacle may catch the crowd’s attention but it is the central love affair that captures its empathy. Suggested by Giacomo Puccini’s opera, Madama Butterfly, Miss Saigon is the story of Kim, forced into prostitution when her family is slaughtered in a military action, and Chris, an idealistic American soldier sickened by all he sees in Vietnam.

They are decent people caught up in the craziness of a world spinning off its hinges. For one brief, passionate moment, they find themselves in each other, only to lose whatever future they might have had in the Americans’ frantic evacuation of Saigon.

Chris goes back to a new life, a new wife and nights filled with terrifying dreams. Kim has nightmares of her own, as she struggles to survive in a Communist-ruled Vietnam and raise the son that Chris doesn’t know he has. She is sustained by the dream that some day Chris will come back and take them to America.

He does return, but their reunion isn’t what either expects. The affair, as in the opera, ends in tragedy and the sound of audience members reaching for their Kleenex.

Miss Saigon‘s splendor may be its backbone, but it is its cast that always has given it its heart. Few who saw them will forget the original Kim and Chris, Lea Salonga and Simon Bowman, or Jonathon Pryce as the Engineer, the oily Saigon pimp who serves the musical as a sort of demented emcee.

At Gammage, those roles are beautifully filled by Kristine Remigio, Steve Pasquale and Joseph Anthony Foronda. Remigio is a slip of a thing, a Dresden doll recast in an Eastern mold. By turns winsome, frightened, determined to survive, she is an innocent adrift and who better to bring her to shore than the handsomely stalwart Pasquale?

Their voices – hers a belter but capable of subtlety; his an almost lyrical tenor – make the most of the show’s only memorable song, the haunting Last Night of the World.

Foronda, if anything, is better than Pryce, though to many that will be heresy. He has all of the English actor’s scheming sliminess as the Engineer, but there is an unexpected vulnerability, a glimpse of the child seduced by the bright promise of tomorrow and ultimately betrayed.

That is the redeeming value of Miss Saigon. It reminds us that others don’t always see us as we want to be seen or, for that matter, as we see ourselves.

The comic-book cynicism of the Engineer’s big number, The American Dream, is rooted in the arrogant attitude that everything American is better. Nothing can live up to that promise and it is no surprise that a couple of Europeans, frustrated and angry at the way their culture is decking itself out in Levis and eating Big Macs, should pen a bitter retort.

Sad to say, the Ugly American is not a myth. Miss Saigon is its legacy.

-30-

JANUARY 14, 1968. Clipping from the Arizona Republic.