An actress – a real, honest-to-goodness actress – is harder to capture than a butterfly on a windy day. Especially if you’re trying to catch her with a net of words.

I can no more reduce Debra K. Stevens to a paragraph than I could climb Mt Everest. Frankly, the climb would be less of a challenge. She is cosmopolitan, a sophisticate, yet I have seen her be so folksy, I wanted to cross my feet and say “Aw, shucks.” I have been lulled by her gentleness, and in the next second, shocked as she tossed a tantrum that scorched the room (Helen Keller, “The Miracle Worker”; Mae, “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof”).

She has slithered across a web, a defiantly sensual, just a bit dangerous, spider, though it’s children in the audience and a loveable pig in the wings (Charlotte, “Charlotte’s Web”). She has been a disembodied voice, living in the sound system, who captivates an audience just the same (the unseen Narrator, “The Velveteen Rabbit”).

In her personal life, this Southern belle seems eminently sensible, but flick that inexplicable switch, and she can be as eccentrically southern-fried chicken as Mame trying to please Beau’s relatives. (Arlene, “Next Fall”). Or she can behave as if the rules of logic didn’t exist and come across as the essence of common sense (“Mrs Whatsit, “A Wrinkle in Time”)

The gist of all that is, if you’re trying to get a handle on Debra from a seat in the audience, pack it in. This is a genuine, 24k actress. She is the character she inhabits, the imaginary made real for however long the show lasts.

Listing the best who ever trod the boards in the Valley? Add her name. Profiling the woman? Best leave magic alone.

Q&A

If you had to eat one type of food for the rest of your life, it would be…

Memphis BBQ…… and chocolate.

And now for some Cat in the Hat fun.

And this just in from 2011’s Lily’s Purple Plastic Purse. Post

September, 2002. “Charlotte’s Web.” Article by Kyle Lawson in the Sept. 15 issue of the Arizona Republic.

Goodness, the get-ups Debra K. Stevens gets into. Take her latest costume, for Childsplay’s lavish revival of Charlotte’s Web. Wasn’t Pink wearing something like that at the Video Music Awards? Or maybe it was Lil’ Kim.

A bustier with eight fuzzy dangling legs is just too cool.

Are you laughing? Stop it. You can’t be a spider without eight fuzzy dangling legs, and Stevens is Charlotte, who would be queen if spiders put stock in royalty. Everyone kowtows to her, especially the barnyard residents in E.B. White’s beloved children’s tale.

The obeisance is deserved. Charlotte’s a good-hearted, if busy-bodied soul, always dispensing advice and making the world safe for pigs. And would you take a gander at those abs? Spider-Man should look so good.

“I was climbing on the web for five hours last night,” Stevens says modestly. “Upper body strength is where it’s at.”

She breaks into an unspidery fit of the giggles.

“Of course, I sure feel it this morning.”

Stevens is an integral part of the Childsplay acting ensemble, widely regarded as the finest such troupe in the Southwest, if not the whole United States. She’s also a regular with other Valley companies, most recently appearing in Dinner With Friends for Actors Theatre.

A spider? Well, that’s special even for this versatile actress, who also played the role in a 1996 Childsplay incarnation.

“That time, I had a little spider living in my living room window,” she says. “Generally, I’m pretty murderous toward spiders, but I couldn’t bring myself to get rid of it. I would hang out by the couch and watch it, looking for pointers.

“My parents came to visit and my mother did what she usually does: She cleaned my house. ‘Where’s the web?’ I asked. ‘Oh, I took care of it,’ she said. ‘My God, you’ve killed Charlotte!’ I cried.”

Finding the inner arachnid is not as easy as Stevens makes it look.

“The only way to prepare yourself is to get up on that web and crawl around and feel what it’s like,” she says. “It’s six years later, you know, and I needed to do a bit of extra stretching. It’s not just upper body. It’s really demanding on your legs when you try to create a shape that looks spidery.”

Not to worry. She has what she calls the “Childsplay advantage.”

“As actors, we’ve worked together for years, and that sense of relationship that is in our lives works to our advantage onstage. This play is about friendship, and when Scott (Withers, who plays Wilbur the Pig) looks up at me and says goodbye, it’s heartbreaking.”

Although Stevens will be busy for the next several weeks bringing Charlotte to life on the Herberger Theater Center stage, she can see herself taking on a non-children’s role before the season’s out.

“But I don’t know if the other artistic directors do,” she says wistfully. “We’ll see if anything aligns for me. I haven’t signed on anybody’s dotted line yet — or been asked to.”

Though best known for her work with Childsplay, Debra has played many adult roles for local companies. One of her most powerful performances came as Mae, the embittered “Sister Woman,” in Actors Theatre’s production of Tennessee William’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Here is Kyle Lawson’s review from the Sept. 15, 2003 issue of the Arizona Republic.

Unrequited love is a festering sore. It leaves a wife empty, a husband lost, a father frustrated, a brother envious. Too much of it? Too little? It makes no difference. Love denied is malignant. It infests a family, rotting the ties that should bind.

Such is the cancer that is destroying the clan inhabiting “28,000 acres of the finest land this side of the Nile Delta” in Tennessee Williams’ drama, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, which opened Friday in a powerful Actors Theatre revival at the Herberger Theater Center.

A tumor is draining the life from Big Daddy, the family patriarch. Other lesions, just as deadly, are eating away at Brick, his alcoholic son, and Maggie, Brick’s sex-starved wife.

Why has Brick denied Maggie his bed? Did he commit sodomy with his friend Skipper? Is it necessary to lie to Big Daddy about his condition? The days on the play’s Mississippi plantation are filled with questions and the nights with no answers.

Scarily, the infection is spreading. Gooper, Brick’s older brother, is soured after years of feeling unwanted and second best. Mae, Gooper’s brood mare of a mate, is fearful her progeny will be cheated of the family wealth. She pours forth bile with each afterbirth.

Even Big Mama, the matriarch, is at risk: she is in terminal denial, refusing to believe that Big Daddy has slept with her for 40 years but never once loved her.

These people sound like monsters. They are monsters. But try ignoring their relentless march to self-destruction. Death, physical death, the death of the soul, hovers over the piece like a miasma from the low-lying fields just offstage — and death demands that attention be paid.

Although it has a reputation for sexiness, Cat is graphic only in terms of language and innuendo. It has more on its mind than rutting; it is an almost surgical dissection of mendacity, the lies that people tell each other to get from one day to the next.

It takes uncommon actors to make something so formidable work, and director Matthew Wiener has filled his cast with uncommonly good performers.

Who is best? The Maggie of Natalie Messersmith or the Big Daddy of Benjamin Stewart? It’s a close call as each delivers a career-defining performance. The edge must go to Stewart, whose every speech reveals a life-engorging man brought low by fate and his frustrated ambitions for his son.

That is not to deny the power of Jason Kuykendall’s Brick, Pamela Fields’ Big Mama, Gene Ganssle’s Gooper or Debra K. Stevens’ Mae, each of whom delivers the emotional goods.

For all its overwrought drama, Cat is funny and Wiener carefully orchestrates the laughs, just as he has structured the action in a series of visual compositions that tell as much about the characters as the words they deliver. He, too, can claim this as a career high.

Excerpt from 2002 article by Kyle Lawson, Arizona Republic

Swordfighter extraordinaire, poet and philosopher known throughout Paris as a one-man crusade for truth and beauty—that’s Cyrano de Bergerac. His outrageous courage is surpassed only by his outrageous proboscis—or as some would say his GIGANTIC nose! Cyrano, the classic tale of the ultimate love triangle, will come alive on stage at the Paul V. Galvin Playhouse (ASU Campus) Feb. 15 – March 3, 2002. This is a first-time collaboration between the Herberger College of Fine Arts Department of Theatre and Childsplay.

This new adaptation of Edmond Rostand’s Cyrano is written by Barry Kornhauser and is suited for young audiences (over 11 years of age). Directed by Childsplay’s David Saar, this production features an all-star cast with Jere Luisi as Cyrano; Debra K. Stevens as the object of his desire, Roxanne; and ASU student Kyle Sorrell as the handsome Christian. The play’s cast dons the costume creations of ASU’s Connie Furr-Solomon and performs in the Baroque literary world as designed by Robert Klinglehoefer.

AN INTERVIEW WITH KYLE LAWSON IN THE JULY 8, 2001 ISSUE OF THE ARIZONA REPUBLIC

Actors are chameleons. But even among these changeable artists, Debra K. Stevens leaves audiences wondering whether they’ve ever seen her before.

With each new role, she changes completely. The alluring femme fatale becomes the waspish spinster, the pre-pubescent boy turns into the wisecracking chicken.

Take this season.

Stevens was the bitter wife of the Marquis de Sade in Quills, Bill the Chicken in Time Again in Oz, the boy in The Velveteen Rabbit, the enigmatic, sexually promiscuous Maya in The Archbishop’s Ceiling and the well-intentioned social worker, Sarah, in The Boxcar Children.

Currently, she’s enraging audiences as the liberal Catherine, who dares to champion the rights of the child molester who lives next door in Jane Martin’s shocker, Mr. Bundy.

QUESTION: That’s quite a collection of women … and boys … and birds.

ANSWER: I’m an equal opportunity actor. I’ve been spiders, chipmunks, a tap-dancing cow … it’s feast or famine. This year, I’ve had the opportunity to do some fabulous parts, but other years, nothing works out. You can’t plan on anything in this business. What comes up, comes up.

Q: Catherine has to be one the most challenging women you’ve portrayed. Even though she’s fearful for her child’s safety, she believes that the molester has rights, including the right to live where he wants.

A: My first response, after reading the script, was, “Oh, my God, this is every liberal’s nightmare.” She has to walk the walk. It’s easy to be philosophical about how you feel when the situation is removed from you, but when it’s right in your back yard. …

Q: What would you do?

A: I would like to think I could be Catherine and have the moral fiber to follow through on my convictions.

Q: Does the prospect of playing such different characters make you nervous?

A: What you look for are things that rattle your cage and, so, when you find them, you’re mostly excited by the challenge. But yes, it’s a little scary, too. Of all the characters I’ve played this season, Maya was the greatest stretch for me. I’ve always wanted to do an Arthur Miller play, and I knew it wouldn’t be easy, but Maya was all-consuming.

Q: She’s certainly no Bill the Chicken. You were a perfect cluck. Where did that come from?

A: (Laughing.) I haven’t a clue. I got in touch with my inner chicken, I guess.

Q: Most of your Valley career has been spent with Childsplay. Few actors would invest 19 years of their life in one company.

A: I’d do it again, given the same circumstances. I adore kids. They’re more interesting than most adults I know. One of my favorite actors was the late Danny Kaye. He spent much of his time performing for children or caring for them through his work with UNICEF. I remember playing his records when I was a child. My dad traveled a lot, and he (Kaye) became sort of a surrogate father. When my dad came home, it was like having Danny Kaye to myself, because my father is such an incredibly playful man. I don’t know. There’s a connection there somewhere. Performing for children and making them happy seems like a really good thing to do.

MARCH 1999. “Island of the Blue Dolphins“ Review by Kyle Lawson, Arizona Republic

Island of the Blue Dolphins is crammed with the sort of derring-do that moves boys to the edge of their seats. Girls, too, since the Childsplay production at the Herberger Theater Center features a plucky heroine in place of the usual hero.

The swashbuckling action and rustic humor are complemented by moments of great visual beauty. Waves crash against the shores of a remote northern island. A sailing ship plunges into a storm. Panoramic sunsets transform themselves into basins of stars.

All this pales beside the play’s scenes of violence. Marauding otter hunters massacre the inhabitants of a native village in a stylized, strobe-lighted ballet. Later, a pack of wild dogs surrounds a boy who has no place to run. As the dogs lunge, the lights dim. When they come up, the youth’s body lies crumpled against the rocks.

It is a cruel message. The world is a wondrous, savage place, and children are at its mercy. To some adults in the audience, it seems shockingly grim.

This is where Childsplay separates itself from other children’s troupes. Director David Saar and his ensemble of actors refuse to take the easy route. They challenge their viewers to confront the demons of childhood, in this case, death, feelings of loss and the terror of being alone, and perhaps to learn a lesson or two about dealing with them.

Take the killing of the boy. Playwright Brian Burgess Clark, working from the Newbery Medal-winning book by Scott O’Dell, asks his audiences to look beyond the horror to contrast the boy’s death with the slaughter of his family at the hands of the hunters.

The hunters murdered the natives out of greed and hatred. The dogs killed because their pups were hungry. Is the dogs’ behavior different from that of the tribe, which kills birds and sea creatures to feed and clothe itself?

There is a natural order to things, Clark seems to suggest, even if it is harsh. To survive, children must learn to live in harmony with it. Sophisticated reasoning is required here, but the beauty of it is that the youngsters in Childsplay’s audiences get it. Sometimes, their parents have to help, but that’s the point. Theater, the best theater, starts conversations.

After the massacre, the survivors abandon the island. Eleven-year-old Karana and her young brother are left behind. After the boy’s death, Karana grows to womanhood, with only the ghosts of her ancestors and the island’s animals as companions.

She survives, learning by instinct and trial and error how to bend the elements and the wildlife to her will. She befriends a wild dog and, later, a Russian girl who comes to the island with other hunters. Slowly, she purges herself of her fears and bitterness, and comes to accept the world that God has given her. When she is rescued and taken to a distant mission station, she realizes that her experiences have made her strong. She has taken responsibility for her life.

Alejandra Garcia, an actress of Mexican descent, navigates this journey with charm and considerable skill. Smart, feisty, yet fearful and vulnerable, her final triumph is sweet, especially for the girls in the audience who rarely see this kind of role model on stage.

The remainder of the Childsplay ensemble play numerous roles. All are good, but Debra K. Stevens’ Russian girl is a standout, along with Jon Gentry’s and D. Scott Withers’ comic sailors.

The real stars here are the production’s designers. Rebecca Akins’ costumes, made entirely from feathers and natural fibers, are stunning, as is Paul Black’s atmospheric lighting, with its swirling patterns that help audiences track the passing years. Gro Johre contributes another of her imaginative scenic designs, evoking wave-eroded island ledges, windswept promontories and smoky, incense-filled churches. Frances Cohen, artistic director of Center Dance Ensemble, makes a notable Childsplay debut with several abstract ballets inspired by native dances.

Like all Childsplay productions, Island of the Blue Dolphins improves as children and parents discuss it in the car on the way home and over the breakfast table the next morning. In the theater, it provokes wonder, laughter and – fair warning – moments of genuine fright. It is afterward, with the aid of recollection, that one realizes it also has shed a little light on a dark world.

FEBRUARY, 1999. CHILDSPLAY. THE HIGHEST HEAVEN. Arizona Republic Review by Kyle Lawson

Too often, children’s theater is pablum: nutritious after a fashion but impossibly bland. Or worse, it’s junk food: the recycling of the same imagination-starved fairy tale.

Never at Childsplay. The company would rather stuff its young audiences with fare too sophisticated for its palate than blunt developing taste buds with cloying sweetness.

In The Highest Heaven, a world premiere at the Tempe Performing Arts Center, Jose Cruz Gonzalez, the troupe’s playwright in residence, has created a fable that is as appetizing for adults as it is for young people.

It is a cautionary tale of greed, passion and cruelty, and, at the same time, a magical enchantment that sends the senses soaring along with the monarch butterflies that are the focus of the story.

The settings are abstract, the plot revealed in shifting flashbacks. Director David Saar paces events quickly. The audience must pay attention to keep up, and to the credit of Gonzalez and the Childsplay artists, 2- and 3-year-olds were as raptly attentive at Saturday’s matinee as their older brothers and sisters.

Eavesdropping on the way to the parking lot, it was clear to this critic that everyone “got it.” Saar and his company risk going over the heads of their young audiences, but The Highest Heaven is proof that it is better to fail children at that level than to succeed by condescending to them.

Gonzalez’s play is the story of Huracan, a 12-year-old (Steven Pena) who is separated from his mother (Alejandra Garcia) in one of those forced deportations of aliens that blighted the government’s reaction to the Depression. He finds himself in a Mexican village, where he comes into conflict with the rapacious Dona Elena (Debra K. Stevens) and her toadying sons and nephews (all played by Jon Gentry).

Huracan finds shelter with El Negro (Ellen Benton), who, as it turns out, also has been evicted from America for reasons that the elderly Black hobo refuses to discuss. El Negro has become the protector of a forest reserve where monarch butterflies go every year to mate amid the lush vegetation – a verdant wonderland that Dona Elena wants to clear-cut to increase her already overflowing coffers.

Huracan is like one of the butterflies’ get, trapped in a chrysalis of naivete. With El Negro’s help, he breaks the bonds of childhood but discovers that freedom bears a draconian price tag. There are hard truths to be learned about ecology and economics, decency and friendship. The most painful lesson, and the most liberating, comes in realizing that life’s journey inevitably ends in death.

Gonzalez never belabors the moralizing or the butterfly metaphor, yet, when the monarchs spiral heavenward at the close (an exhilarating bit of stage magic), there are cheers from the audience and an understanding that Huracan has begun the perilous but life-affirming migration to adulthood.

Childsplay audiences have come to take excellent performances for granted, and the quintet of actors in The Highest Heaven does not disappoint. But Stevens’ versatility is exceptional even for this troupe. When last seen, she was the plucky young hero of The Velveteen Rabbit. Here she is a harpy from a child’s darkest nightmare, a chilling, malevolent presence that dominates the play even when off stage.

After more than a decade of dealing with Childsplay audiences, Stevens knows how far to take this. Just when Dona Elena is in danger of seriously frightening young playgoers, the actress does something so foolishly comic that they are startled into laughter. This is children’s theater, and she never forgets it – but at the same time, she never plays her audience for fools.

The same can be said of the company’s designers. The physical production represents state-of-the-art technology, but the effects are never used for cheap effect. Even at its most dazzling, the magic in The Highest Heaven has meaning. Sometimes, that meaning is subtle, but the assumption is: If the younger members of the audience don’t get it, the older ones will explain it.

It is a testimony to Childsplay’s skill at making theater that very little explanation is required.

1987. CLARISSA’S CLOSET. CHILDSPLAY.

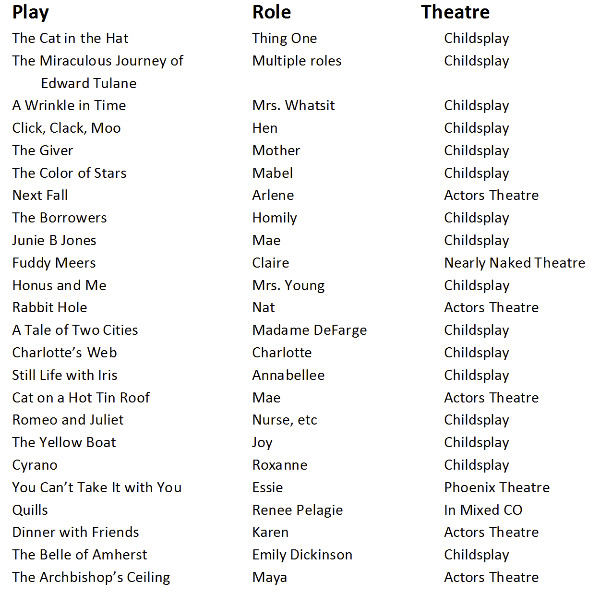

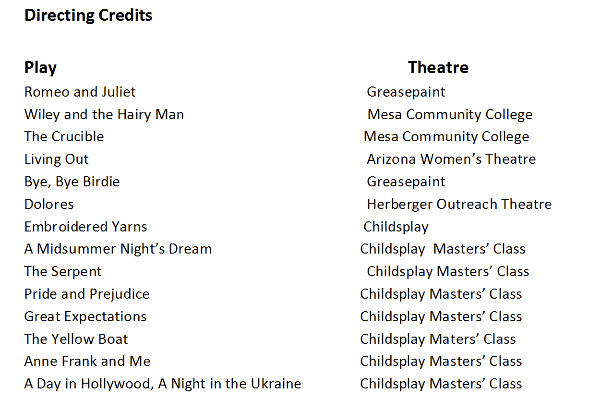

SELECTED CREDITS